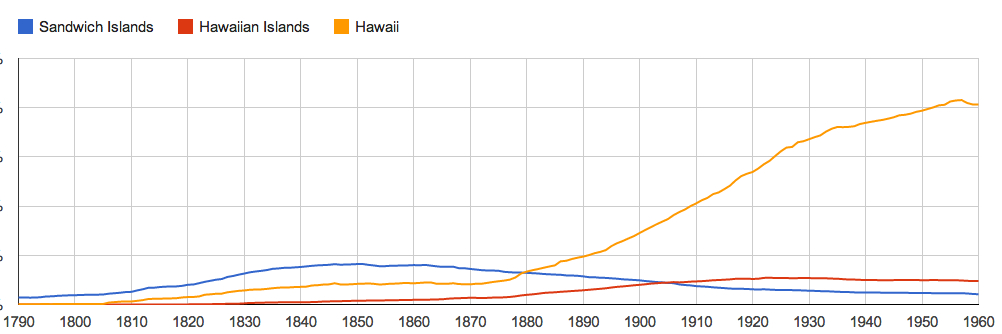

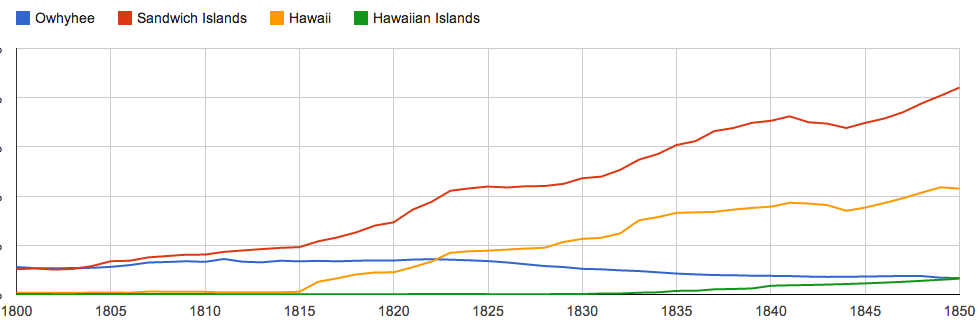

Tonight, ESPN is airing what looks like a cool documentary about Eddie Aikau that delves into ongoing conflicts between Native Hawaiians and the United States. I figured this made it as good of a time as any to write a continuation of an earlier post, which looked at the history and politics of the nomenclature of the islands. By the end of the nineteenth century and despite the persistence of the British designation of Sandwich Islands among outsiders, in its official documents and diplomatic relations the Kingdom of Hawaii invariably referred to the archipelago as the Hawaiian Islands. In January 1893, the Hawaiian Kingdom was overthrown and Queen Lili’uokalani was deposed by a moneyed cabal pushing for American annexation. This resulted in the relatively brief and tumultuous period in which the islands were known as the Republic of Hawaii (1894-1898). Despite resistance by both Native Hawaiians and anti-imperialists in the United States, the so-called Newlands Resolution that provided for “for annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States” was controversially approved by Congress and signed by President McKinley on July 7, 1898.

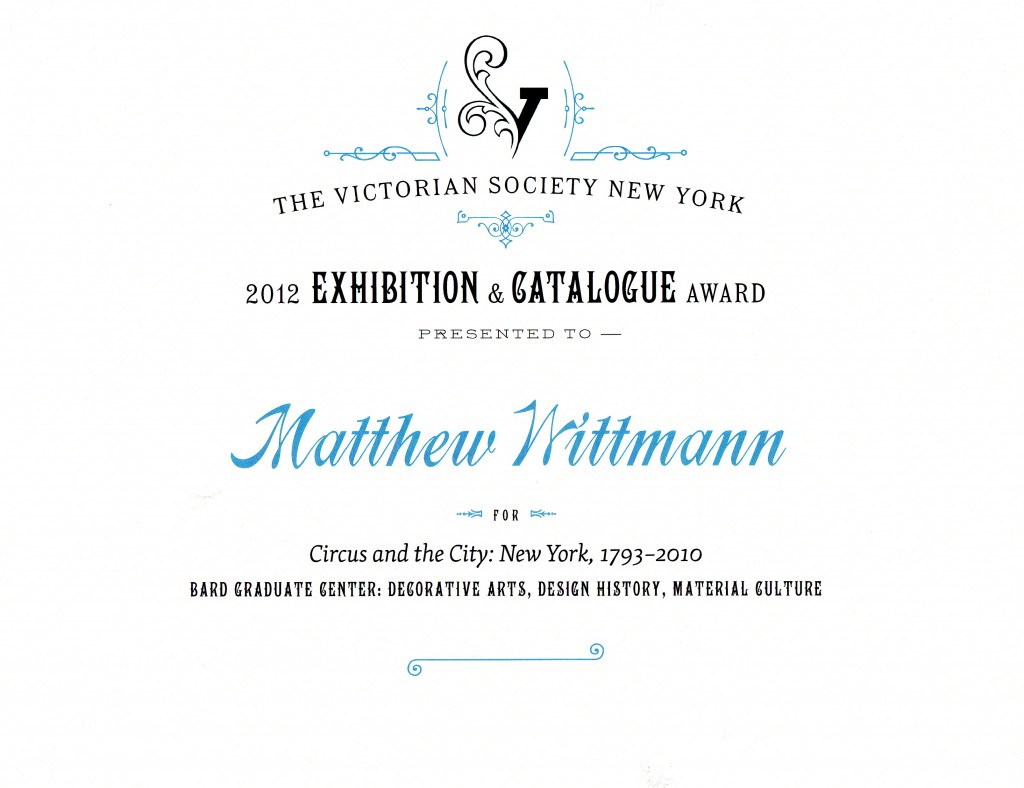

The Hawaiian Organic Act of 1900 subsequently designated the islands as the “Territory of Hawaii” and officially made them an “organized incorporated territory of the United States.” Although political and legal struggles over the islands were ongoing, this more or less settled the nonmenclature issue for a time as the graph below shows.

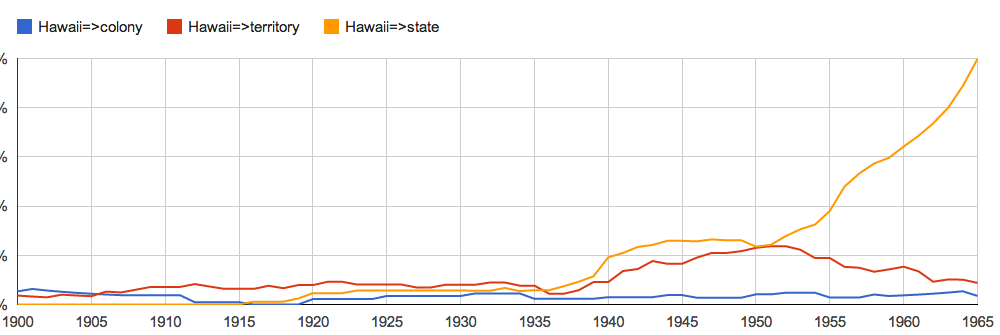

After 1900, the Anglo-inspired “Sandwich Islands” slides into obscurity and the singular Hawaii ascends as the preferred designation. But if the name of the islands was for the time being no longer a significant point of contention, its political and legal status continued to be. Historians have generally located “the birth of an American Empire” in the last decade of the nineteenth century when U.S. foreign policy took a distinctly imperial turn and overseas intrusions multiplied. Whatever the merits of this rather creaky interpretation, American exceptionalism dictated that the United States was manifestly not a colonial power. This meant that the imposition of American rule needed to be refigured as something benevolent, and welcomed by Hawaiians (for more on the complicated cultural interactions through which this was accomplished, see Adria Imada’s aforementioned study). But it was also an issue of terminology. To be clear, the relationship between the United States and Hawaii from 1900 forward was clearly a colonial one, but this was obfuscated by the classification of the islands as an “organized incorporated territory,” which ostensibly put Hawaii on a path to statehood. And yet a combination of racial prejudice, island politics, and U.S. satisfaction with the status quo ensured that statehood was consistently deferred. Hawaii’s status became a more pressing issue as the end of World War II approached and Franklin Roosevelt’s vaunted anticolonialism roiled the postwar plans of the Allies. In 1946, Hawaii was placed on the United Nations list of “non-self-governing territories.” Although it obviously remained under American jurisdiction, the list was viewed by many as a precursor to political independence and the United States was required to submit annual reports on conditions there and to support the development of self-government going forward. The United States of course had no intention of parting with what was perhaps its most strategically significant overseas territory, but Cold War politics and widespread decolonization made Hawaii’s status an increasingly problematic concern for the U.S. in the 1950s. Statehood offered a potential solution, but the politics of Hawaiian statehood proved contentious both in the islands and on the mainland.

The graph above illustrates something of the confusion, charting how Hawaii was variously described during its time as an American territory (note the post-WWII spike in discussions about statehood). As momentum in the United Nations was building for a resolution granting independence to colonial countries and peoples (resulting in the landmark Resolution 1514 in 1960, which unanimously passed the General Assembly with the U.S. and other major colonial powers abstaining), the Eisenhower administration was finally able to push through the Hawaii Admission Act. The act put the matter of statehood to a vote in the summer of 1959, and despite some noteworthy Native Hawaiian opposition, it was overwhelmingly approved. The United States duly notified the U.N. Secretary General and Hawaii was removed from the list of non-self-governing territories in September. On August 21, 1959, Hawaii was formally “admitted” to the Union. Despite some continuing discontent, statehood seemingly resolved for a time what exactly the islands should be known as, i.e., the State of Hawaii.

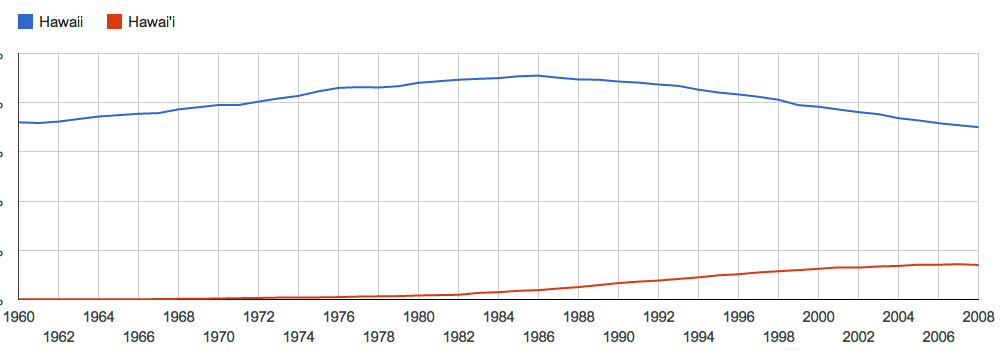

This proved short-lived. In the 1970s, the Hawaiian Renaissance and the concomitant rise of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement again threw the name of the islands and their political status into question. One result of the political ferment and the revived interest in Hawaiian language was a push to return to the putatively traditional pronunciation and orthography of Native Hawaiians. This involved a shift from Hawaii (huh-WY-ee) to Hawai’i (huh-WAH-ee or huh-VY-ee) with the ‘okina marking a glottal stop and the pronunciation of the middle syllable as either a w or soft v still in dispute. However it is pronounced, the standard spelling in academia and Native Hawaiian circles is now Hawai’i, and it would seem to be gaining purchase in the larger culture as well.

What the future holds remains to be seen, but the two-hundred-year struggle over what the islands should be called aptly demonstrates the link between language and power. Ultimately, what’s in a name is politics, and given its history, the nomenclature of the Hawaiian Islands will undoubtedly remain contentious.