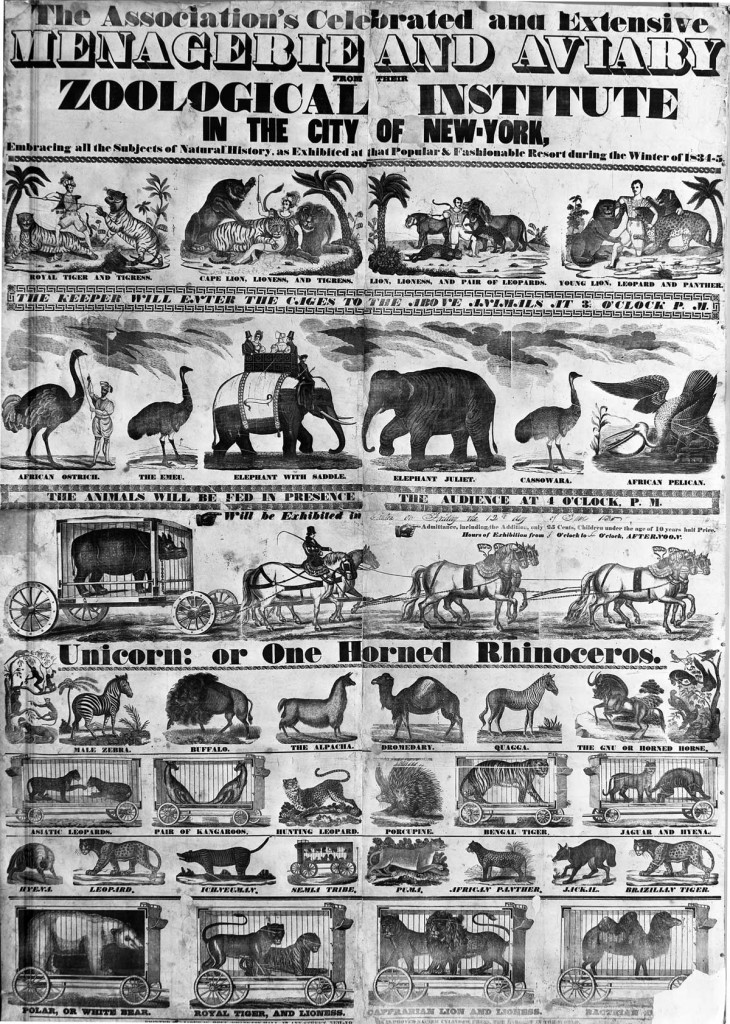

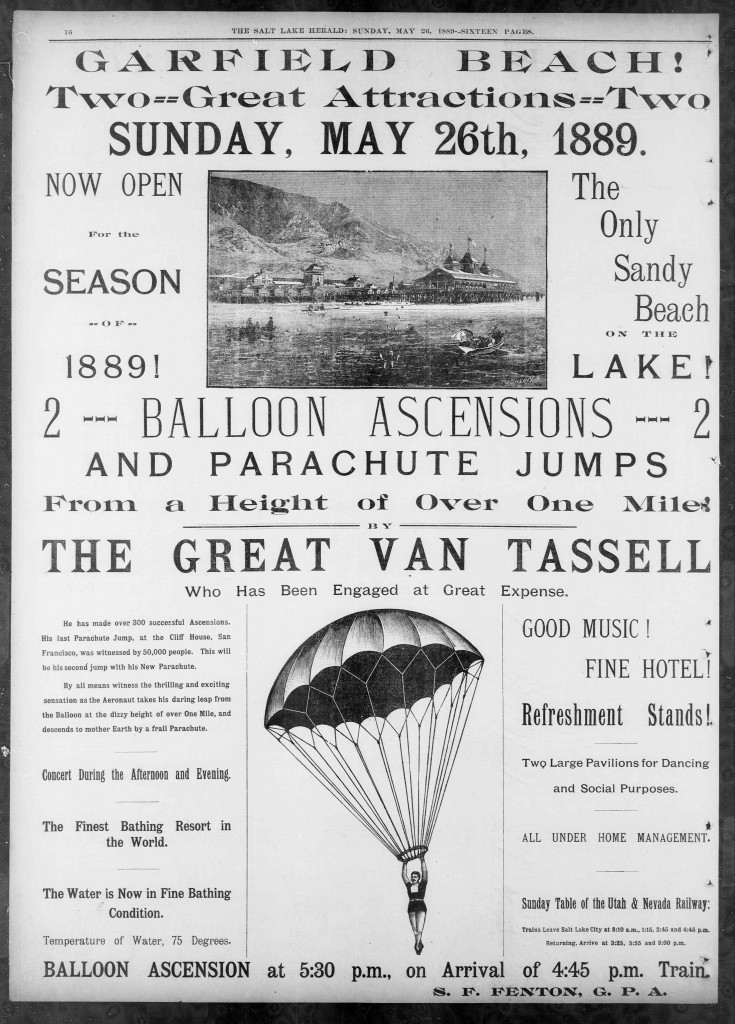

Joseph Lawrence was born in 1863 in Salem, Ohio and owned a hardware business until he was 24, when he somewhat unaccountably began a new career as a daredevil balloon ascensionist. The French inventor and aviation pioneer Jean-Pierre Blanchard first brought the practice of ballooning to the United States in 1793. Unmanned balloons were used by American circuses as early as the 1820s for advertising and publicity, but it wasn’t until the 1870s that the great era of circus ballooning got started. Aeronauts, as they were often styled, would ascend a mile or so into the air in a hydrogen balloon, performing tricks on a trapeze dangling from the basket and then parachuting to the ground for the finale. It was also, perhaps curiously, one of the few lines of circus work in which African-Americans were accepted and so-called “colored aeronauts” were fairly common. Some shows had multiple balloons upon which customers could pay to ride during the day, but Joseph Lawrence made his name as a daredevil aeronaut. Beginning in 1887, he traveled around the country giving exhibitions, eventually adopting the “Van Tassell” surname after joining forces with Park Van Tassel, a competing aeronaut who made a name for himself performing around the American West.

The Van Tassell Bros. troupe made plans for an ambitious tour through the Pacific during the fall of 1889. After performing in San Francisco, Joseph Lawrence “Van Tassell” arrived in Honolulu in late October and made his first ascension on November 2, safely parachuting to the ground in front of a crowd of 500 or so spectators. After his initial success, the newly minted pioneer of Hawaiian aviation planned a follow-up performance in honor of King King David Kalākaua’s birthday on November 16. Unfortunately, the wind picked up that day as the balloon rose into the sky and although he was able to successfully cut loose and deploy his parachute, a gust carried Joseph out to sea. He landed some miles from shore and drowned before help could arrive.

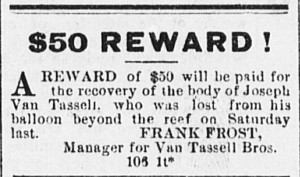

Despite a hopeful advertisement from the troupe’s manager, Joseph’s body was never found. And so in relatively short order, Joseph Lawrence went from the first flyer on Hawai’i to the first aviation fatality. Park Van Tassel continued to tour around the Pacific in the years that followed. Another performer with whom he was affiliated, Jeannette Van Tassel (variously described as his wife or daughter), was killed after a fall at Dhaka (Bangladesh) in March 1892, after which he finally retired from the balloon business.

On balloon and the American circus, see Bob Parkinson, “Circus Balloon Ascensions,” Bandwagon (Sep.–Oct. 1964), 3–6; on the many tragedies that accompanied them see William L. Slout, “What Goes Up…Comes Down, Bandwagon (March–April 1996), 22-27.