The centennial of the International Exhibition of Modern Art, better know as simply the Armory Show, has prompted a renewed wave of interest and a number of competing exhibitions about what many regard as the most important event in the history of American art. A full list of exhibitions and related publications can be found here, but perhaps the most prominent of these shows is the New-York Historical Society’s Armory Show at 100, which runs through February 23, 2014. I had the opportunity to visit when I was in New York City last week, and I must say that I came away rather disappointed (though the accompanying website is useful). Although the NYHS was able to get some fantastic material on loan for the exhibition, the overall interpretation was creaky and its organization was at times simply confusing.

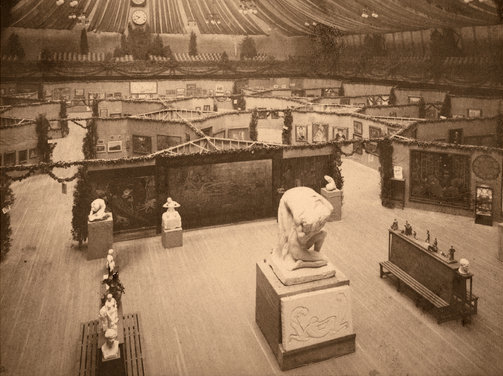

First and foremost, it is not clear where the exhibition actually starts, with a small gallery of material about “Organizing the Armory Show” and a hallway full of contextual information about New York City in the early twentieth-century awkwardly positioned before the main gallery (I am still not sure if I was meant to go through these before or after the art). Whatever the case, the central gallery includes some 100 works drawn from over thirteen hundred pieces that appeared in the 1913 exhibition. One thing that is made very clear from the beginning is the overall theme, which promises “Modern Art & Revolution,” but much of what follows belies this bold promise and the conflation of politics and aesthetics is problematic throughout. The NYHS exhibition is roughly structured along the same lines as the original show, but the very truncated wall texts deal in such generalities that it is sometimes difficult to get a strong sense of either the historical exhibition or the contemporary interpretation being proposed.

One salutary feature of the present exhibition is its fidelity to representing the wide range of art works that appeared in the Armory Show, much of which was neither revolutionary nor particularly modern. The American painter Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917) and French Symbolist Odilon Redon (18401-1916) were among the most well-represented and received artists, and neither are particularly well-known today.

My favorite paintings in the exhibition (and it is almost entirely paintings) were those by what I would call the American avant-garde. George Bellows’ The Circus, Robert Henri’s Figure in Motion, Arthur B. Davies’ Line of Mountains, and John Sloan’s McSorley’s Bar are all wonderful paintings by artists identified with the so-called Ashcan School. All of these artists were also “revolutionary” and “modern” in their own way, but the framing of the exhibition is so narrowly focused on celebrating an ostensibly sui generis European modernism that it effectively marginalizes innovative American art. Indeed, this was something that many American artists bemoaned about the the Armory Show at the time, so I suppose it is only proper that this current exhibition similarly elevates the European artists over their supposedly hidebound American counterparts. In short, the NYHS exhibition does not do American artists any favors, and all the Armory Show’s complications and contradictions are elided in favor of the shibboleth that the “new” European art revolutionized American culture in one fell swoop.

One noteworthy section positioned amidst the transition to the vaunted European works is a selection of prints by a variety of artists, ranging from John Marin and Stuart Davies to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Edvard Munch. These delightful prints suggest a much more complementary relationship between European and American art than is elsewhere acknowledged.

Still, in arriving at the exhibition’s version of Gallery I, the infamous “Chamber of Horrors” that featured Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 and Henri Matisse’s Blue Nude, it is easy to see why some visitors found these works so surprising in 1913. The NYHS was able to borrow an impressive array of what was regarded as the more sensational art in the Armory Show, but it is of course impossible to resurrect the shock of the new with what are now canonical works. Count me as skeptical that “everyone” was so stunned by these artworks. Recent scholarship suggests that the response to the Armory Show by critics, artists, and the public was much more complicated than the conventional narrative suggests. Moreover, one of the most tired tropes in cultural history and criticism is the idea that X (film, book, album) shocked the world and/or changed everything. As J.M. Mancini, Christine Stansell, and many others make clear, this supposed cultural and aesthetic revolution had a much longer trajectory.

To be fair, some of these complications are addressed around the edges of exhibition, and I can appreciate why the curators stay so focused on the conventional, if flawed, interpretation of the Armory Show to give the exhibition a certain clarity. But other decisions seem less defensible. The end of the main gallery contains a mixed bag of material that confusingly includes some works from J.P. Morgan’s collection in an apparent effort to show that not all contemporary collectors were interested in modern art, which hardly seems surprising. There are also a smattering of works that do not convincingly address the legacy of the Armory Show in American art, though it is a subject that gets more satisfying treatment in the historical materials displayed in the hall adjacent to the main gallery. I really wish that an effort had been made to integrate the very useful and important contextual material in this hall that both sets the scene and explores the legacy of the Armory Show with the actual art. It would have made for a much more coherent interpretation and introduced a level of dynamism that the simple recreation of the original show in smaller form lacked. Of the other ancillary room on “Organizing the Armory Show,” the less said the better about this text-heavy and generally uninteresting display. In sum, I feel like what the Armory Show at 100 needed was to find a better angle, one that would have integrated the Armory Show art with the other materials into a larger story about the development of American modernism. All of that said, the NYHS has assembled a truly wonderful collection of art, and it is well worth a visit. I should also note that the museum has another exhibition open downstairs called Beauty’s Legacy: Gilded Age Portraits in America, which has a rather more satisfying and focused interpretative line and some really excellent portraits so be sure to check that out as well.

Some final notes. The accompanying catalogue, which has a great roster of contributors, undoubtedly deals with some of the complications and criticisms of the exhibition that I offered above, but its size and price ($65!) precluded me from getting a good look. I will update when I do! There are also some great resources online about the Armory Show for those interested. Beyond the aforementioned New-York Historical Society website accompanying the exhibition, the Smithsonian Archives of American Art has a good collection of primary sources here, and the Art Institute Chicago’s has a neat site here about the Armory Show’s sojourn to the Midwest.