One of the most remarkable aspects of the Teller and Todd Robbins’ production Play Dead is how it illustrates the continuing appeal of what might best be described as “anti-spiritualist entertainment.” The show itself is a loosely structured mix of magic, mind reading, and debunking delivered in a gothic style that is alternately scary and amusing. It certainly provoked a range of lively response from the audience the evening I was at the theater. The performance is difficult to categorize and really must be seen, but the driving force is Robbins, who tells a series of tales based around macabre historical figures and events. The inspiration for the show was apparently the tradition of spook or fright shows that attracted mostly young people in search of a thrill at carnivals or at special midnight shows at local theatres across the country. While some will find undoubtedly find the scares in Play Dead hackneyed, it offers, in its own way, a rather serious meditation on death.

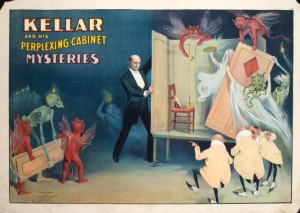

For those interested in nineteenth-century entertainment, it is a delightful continuation of the long tradition of exposing and often lampooning the practices and beliefs associated with spiritualism. Spiritualism was a heterogeneous movement that centered on a belief in the supernatural and that the living could communicate with dead spirits via human mediums. Despite its very public staging, spiritualism has generally not been understood as a form of show business. But as R. Laurence Moore’s notes in his fascinating study In Search of White Crows (1977), part of its appeal was that “mediums could be good theater” and were “another source of entertainment for at least two generations of Americans who liked to explore puzzling situations and gathered to witness anything billed as out of the ordinary (5-6).” Spiritualist entertainers like the Davenport Brothers toured the world with a “spirit cabinet” act in which they were tied up and placed inside of a box with musical instruments that mysteriously played after the lights were dimmed. The noted American magician Harry Kellar (1849-1922), an erstwhile assistant to the brothers, became even more famous for his exposure of this routine.

The overall point is that spiritualism and anti-spiritualism paid dividends at the box office. But mediums, and the magicians that ostensibly worked to expose them, also pushed the boundaries of good taste. Purported communication with dead friends and relatives was obviously a charged subject, and performer’s risked the ire of both the credulous and the critical.

The spiritualist show business existed in an ambiguous space, and critics like Kellar couched their entertainment as a way learn and defend oneself from con games. It is exactly this sort of framework that Todd Robbins adopts in Play Dead, which centers on the tale about Mina “Margery” Crandon (1888-1941), a Boston medium who claimed to be able to speak to the dead. The show runs through a range of spiritualist tricks, including a segment where Robbins somewhat uncomfortably demonstrates the ability to “communicate” with the dead friends and relatives of the audience. I don’t want to reveal too much about the actual performance, but it is both very well written and performed. In short, Play Dead gives a heady mix of cheap thrills and macabre ruminations that is sure to entertain, just as such shows have done since the mid-nineteenth century.