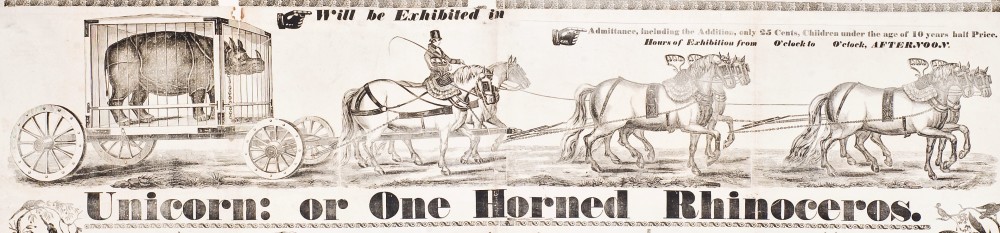

One of the most important and yet mysterious figures in the annals of the American circus is John Bill Ricketts. Although Ricketts was not the first equestrian performer to grace American shores, he has rightfully received the lion’s share of the credit as a founding father of the circus for the scope and duration of his entertainment-related efforts. Much is known about his activities during the eight years he spent in the United States and Canada, from his arrival in Philadelphia in 1792 to his final departure from the country with a small company of performers in the spring of 1800. This is largely due to the diligent research of James Moy, whose dissertation remains the best source on his career. What is less clear was what Ricketts did before and after his time in the United States. Presently the first record of him performing are newspaper advertisements from 1786 for performances at Jones’ Equestrian Amphitheatre in London, but he also spent a significant part of his early career in Edinburgh. The end of his life is even more of a mystery, as his small company was waylaid by pirates near Guadeloupe, but recovered to perform around the Caribbean in 1800-1801. His contemporary and fellow performer John Durang reported that he subsequently “sold all his horses to great advantage and had made an immense amount of money; he chartered an old vessel to take him to England; the vessel foundered and he was lost with all his money at sea.” I have yet to find an independent confirmation of how Ricketts’ met his end.

While much about Ricketts remains unknown, one thing I was able track down was the source of an oft-reproduced but poorly sourced image of the man and his famous horse Cornplanter. As far as I can tell this image was published for the first time in John and Alice Durant’s Pictorial History of the American Circus (1957).  On page 23 there is a small and poorly reproduced image of a mounted Ricketts jumping over another horse held by a groom under a banner reading “We ne’er shall look upon his like again” (an allusion to Hamlet).The Durants credited it to the New York Public Library, but I did not find anything at either the main library’s Print Room or in the Billy Rose Theatre Collection. Google turned up another version of the image on John Bill Ricketts’ Circopedia page, there credited to the Museum of the City of New York. What I found on a visit there was pretty clearly just a modern copy. Where was the original?

On page 23 there is a small and poorly reproduced image of a mounted Ricketts jumping over another horse held by a groom under a banner reading “We ne’er shall look upon his like again” (an allusion to Hamlet).The Durants credited it to the New York Public Library, but I did not find anything at either the main library’s Print Room or in the Billy Rose Theatre Collection. Google turned up another version of the image on John Bill Ricketts’ Circopedia page, there credited to the Museum of the City of New York. What I found on a visit there was pretty clearly just a modern copy. Where was the original?

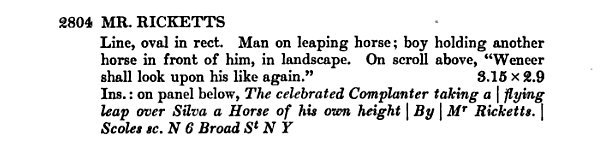

It was clearly a metal plate engraving, which was confirmed by this entry in David McNeely Stauffer’s checklist of American Engravers Upon Copper and Steel (1907):

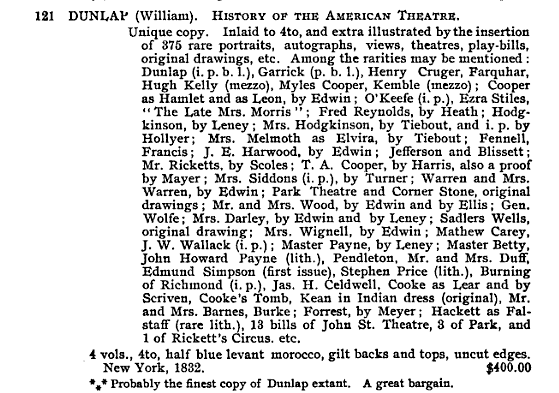

Frustratingly, no source was given. Some further work in Google Books turned up a note about its inclusion in an exhibition at the Boston bibliophile “Club of Odd Volumes” in 1914. It was listed as part of the collection of Robert Gould Shaw and described as an “Extremely Rare Print.” While the disposition of this particular print was not discovered, I was able to find a second allusion to the Scoles engraving. This was from a catalogue of rare books purchased by New York book dealer George D. Smith from the collection of the noted American playwright and stage director Augustin Daly (1838-1899). It details a rare extra-illustrated edition of William Dunlap’s History of the American Theatre (1832), which included among its rarities something described only as “Mr. Ricketts by Scoles.”

Knowing that much of Augustin Daly’s library was in the Harvard Theatre Collection (and indeed this had seemingly been one of the foundational purchases of that collection), I went right to their library catalog, which confirmed that Harvard had Daly’s copy of Dunlap but little else. So it remained for me to take make the trip up there and examine the volumes in person. They are an invaluable treasury of American entertainment history, and a little over 100 pages into volume two, I found the engraving of Ricketts. Although I knew the supposed dimensions, it was something of surprise to see how small the original sepia-toned engraving was. John Scoles was a talented engraver and sometime book seller in New York City from 1793 to 1844 so this was among his earliest works. Ricketts first regularly performed the feat of jumping Cornplanter over another horse “fourteen-hands-high” in 1796 so the engraving likely dates to that year. It is a well-cut and dramatic scene and I was just thrilled to finally find the original. I ordered a scan and it will certainly figure in the upcoming Circus and the City exhibition!

Update: After my request, Harvard put the high-resolution image online here. And it is of course featured in the Circus and the City catalogue, which you can buy here.