The other day a reader sent in an inquiry about an antique circus jug. It is a truly fascinating piece of mid-nineteenth-century English pottery that was manufactured in Tunstall by Elsmore & Forster sometime between 1853 and 1871.

Tunstall was part of the so-called “Staffordshire Potteries” (modern-day Stoke-on-Trent), a center of ceramic production that developed in the late seventeenth century and which became a hotbed of working class radicalism in the 1840s. Elsmore & Forster seemed to have specialized in this sort of large glazed earthenware jug, which measures 14″ across and 10″ in height. The firm produced several different versions of these jugs decorated with popular entertainment motifs that were “transfer-printed” from wood or metal engravings (see other examples at the V & A here and here).

Tunstall was part of the so-called “Staffordshire Potteries” (modern-day Stoke-on-Trent), a center of ceramic production that developed in the late seventeenth century and which became a hotbed of working class radicalism in the 1840s. Elsmore & Forster seemed to have specialized in this sort of large glazed earthenware jug, which measures 14″ across and 10″ in height. The firm produced several different versions of these jugs decorated with popular entertainment motifs that were “transfer-printed” from wood or metal engravings (see other examples at the V & A here and here).

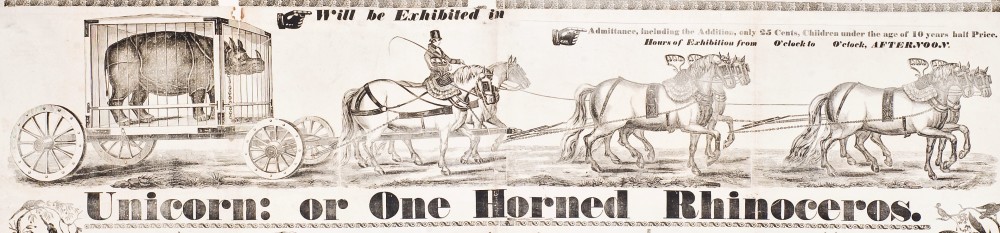

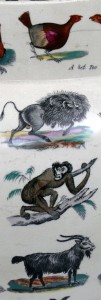

In this case, the engravings were likely borrowed or purchased from a local printer who used these sorts of illustrations in advertising for circuses and menageries. The assorted animals pictured on the jug are based on the work of artist and engraver Thomas Bewick (1753-1828). As I have written about elsewhere, Bewick’s works of natural history, most notably A History of Quadrupeds (1790), were also frequently copied by American printers and feature prominently in many early menagerie posters. A curious range of animals are represented, including an elephant, a zebra, a tiger, a squirrel, a frog, and several domestic house cats. After the outline of the illustrations was transferred onto the surface, they were colored in by hand before the piece was glazed. The line-up of animals are repeated on each side of the jug with a one or two variations and there are some additional ivy leaf and berry decorations inside of the rim and the spout, and along the main handle.

In this case, the engravings were likely borrowed or purchased from a local printer who used these sorts of illustrations in advertising for circuses and menageries. The assorted animals pictured on the jug are based on the work of artist and engraver Thomas Bewick (1753-1828). As I have written about elsewhere, Bewick’s works of natural history, most notably A History of Quadrupeds (1790), were also frequently copied by American printers and feature prominently in many early menagerie posters. A curious range of animals are represented, including an elephant, a zebra, a tiger, a squirrel, a frog, and several domestic house cats. After the outline of the illustrations was transferred onto the surface, they were colored in by hand before the piece was glazed. The line-up of animals are repeated on each side of the jug with a one or two variations and there are some additional ivy leaf and berry decorations inside of the rim and the spout, and along the main handle.

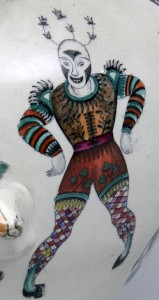

On either side of the smaller carrying handle there are twin images of a clown, identified by various sources as Joe Cashmore. According to John Turner’s biographical dictionary of British circus performers, Joe’s father was a clown named Ike Cashmore and his mother, billed as Madame Cashmore, was a noted tight-rope performer and equestrian. His full name was Joseph Henry Cashmore, and advertisements printed in The Era (a contemporary trade journal for entertainers) listed his skills as: “Comic Knockabout Clown, High Stilts, Juggler, Running Globe, Vaulter, &c.” The clown is the most technically accomplished illustration on the jug, with intricately detailed clothing and checkered tights that required real skill by the colorist to execute. For more on the fascinating world of the mid-nineteenth-century British circus, see The Victorian Clown by Jacky Bratton and Ann Featherstone. The book centers on a manuscript by a man named James Frowde, who performed with Hengler’s Circus in the 1850s, and offers a wealth of information about what life was like for clowns like Cashmore.

And, if you are interested, this wonderful piece of ceramic circus history can be found here for just $2600!