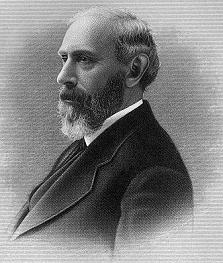

Robert Hewson Pruyn (1815-1882) was an American lawyer and statesman from New York who is the subject of an ongoing exhibition at the Albany Institute. Presently, the fascinating materials on display focus on the years 1862 to 1865 when he served as the U.S. minister to Japan. As a diplomat, Pruyn played a pivotal role in resolving the Shimonoseki War, which was a series of military engagements waged by recalcitrant daimyos (powerful feudal lords) angry with the Tokugawa shogunate’s accommodation of foreign interests. While holding office, he also negotiated a number of shrewd trade agreements that allowed commerce to flourish. And though his diplomatic and economic accomplishments were undoubtedly significant, I was much more intrigued to see a wide variety of ephemera documenting performances by both Euro-American and Japanese entertainers. In the decade that followed Commodore Perry’s expedition in 1853-54, relations between the United States and Japan remained tense, but popular entertainment provided one avenue for cross-cultural exchange and understanding. Indeed, some of Perry’s sailors famously performed a minstrel show at a banquet held when the Kanagawa Treaty was concluded, and the Japanese reciprocated with exhibitions of sumo wrestling, plate-spinning, and acrobatics.

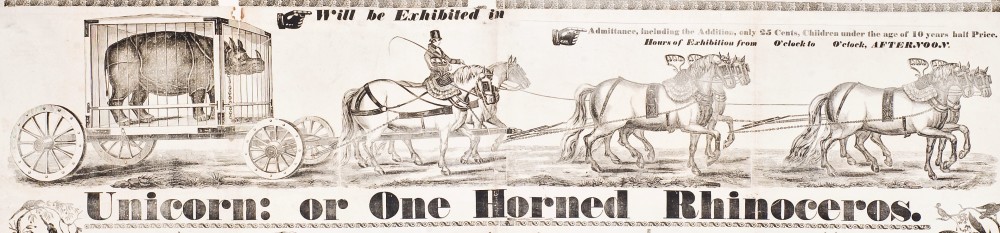

By the early 1860s, Yokohama was a “boomtown,” and performances by both visting Euro-American and Japanese entertainers were patronized by the mixed lot of officials, merchants, and military who congregated around Tokyo Bay. In March 1864, the noted American performer Richard Risley Carlisle (1814-1874), popularly known as “Professor Risley,” arrived in Yokohama with a circus from Shanghai. Risley had ascended to trans-Atlantic fame and fortune in the 1840s with a foot-juggling act that involved spinning and launching limber young assistants high into the air. By the early 1860s, he was touring the Pacific with a small circus comprised of a dozen or so equestrians and acrobats. John R. Black (himself a traveling entertainer that settled in Japan) observed that:

Risley was a man who never did himself justice. He was for some years a resident in Yokohama; but at one time of his life, his name was well known in all the great capitals of Europe and America. I remember him with his sons at the Strand Theatre in London in 1848, when his fame and success seemed carrying everything before him. Apart from his great strength and agility, and the wonderful pluck and cleverness of his boys, which enabled him to present an entertainment as attractive as it was at that time unique, he was peculiarly cut out for the kind of Bohemian life he had chosen. He was a wonderful rifle shot; a good billiard player; up to everything that lithe and active men most rejoice in. He knew thoroughly well the usages of good society, and could hold his own with high or low. His fund of anecdote was marvellous ; and he could keep a roomful of people holding their sides with laughter, without the least appearance of effort, or the faintest shade of coarseness (Young Japan, 1880, 401-402).

Risley’s peripatetic history and his eventual management of a troupe of Japanese acrobats who traveled across the United States and to the 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris have been ably chronicled in an excellent study by Frederik L. Schodt so I will not dwell on that here. What is interesting was how Pruyn perceived Risley’s presence in Japan, and the role of popular entertainment in US-Japanese relations more generally. Again, things were particular tense in March 1864, and Pruyn confessed in a letter that he still regarded it as debatable whether “liberality or exclusiveness” would prevail in Japan. In this context, he saw the arrival of the circus as auspicious, continuing: “American diplomacy first opened this Country partially to foreigners & now that this attempt has been made to thrust us out when once in & slam the door in our faces – why should not an American Circus come to the rescue?” While it is of course arguable just how important Risley’s activities were within the evolving relationship between the two nations, it seems significant to see that the American minister regarded the circus as so relevant. In a follow-up post, I’ll develop this point further by looking at how Pruyn’s perceptions of the Japanese were shaped by his experiences with their sundry forms of popular entertainment.

*** The Robert Pruyn Papers are held at the Albany Institute of History and Art library and a special thanks is owed to Erika Sanger there for bringing these materials to my attention.