One of the most remarkable images in the collections of History Colorado is an ambrotype by George D. Wakely of a M’lle Carolista daringly walking across a tightrope extended over Larimer Street in July 1861. Interestingly enough, Wakely was himself an itinerant entertainer who had first arrived in Denver as part of the Thorne Star Company during the fall of 1859 when the Pikes Peak Gold Rush was in full swing. Charles R. Thorne was a veteran actor and manager who seemingly had a nose for opportunity, having been among the first American entertainers to visit the California gold fields and subsequently touring on the “Pacific circuit” through Hawaii, Australia, and China in the 1850s. Thorne enlisted Wakely, his wife Matilda, and her four children from a previous marriage to perform at the National Theatre in Leavenworth, Kansas, before traveling overland to open at Denver’s Apollo Hall. Although the troupe was initially very successful, Thorne and his son skipped town one evening when business declined, leaving the other members of the company stranded. While some of the Wakely clan continued to perform at the theatre, George opened up the first photography gallery in Denver, having already practiced the trade in Chicago years before. Wakely was a prolific portraitist who also took some wonderful street photographs documenting the city’s growth in the early 1860s.

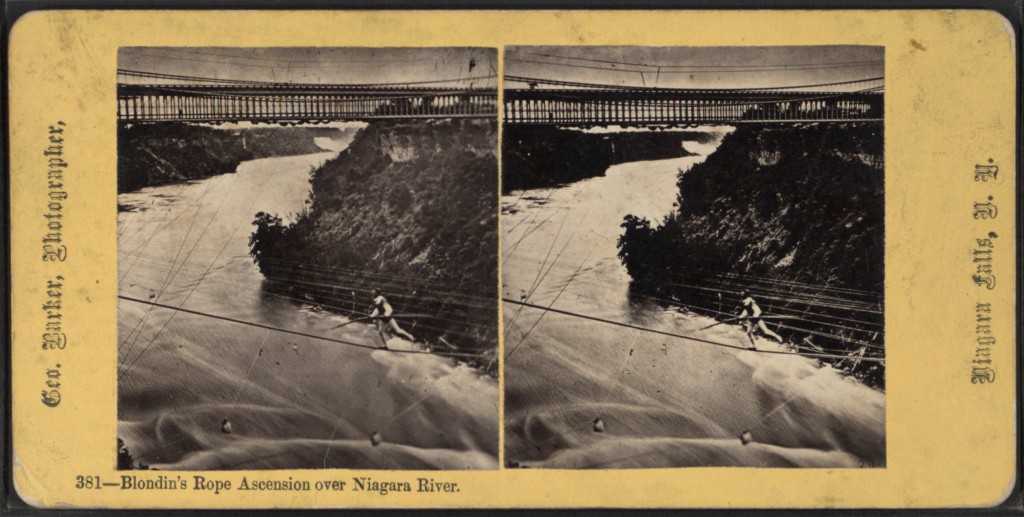

Despite her rather romantic nom d’arena, M’lle Carolista was an acrobat from Cleveland who began performing on the tightrope following the sensationally successful North American tour by the French tightrope walker Charles Blondin during the late 1850s. Although American circuses had long featured tightrope ascensions on their programs, the rather more daring and spectacular feats of Blondin included a celebrated walk across Niagra Falls in 1859. After his initial crossing, Blondin introduced a number of variations such as walking blindfolded, on stilts, pushing a wheelbarrow, and with his manager riding piggyback.

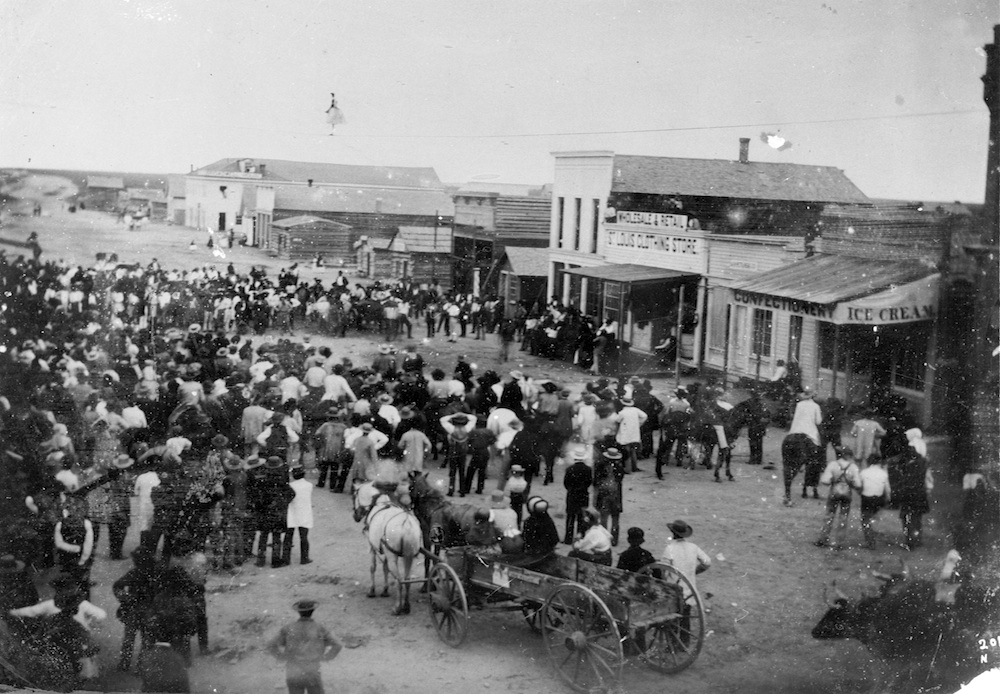

M’lle Carolista performed many of these same feats, billing herself as the “female rival of Blondin.” Her husband and manager was Gus Shaw, and the two traveled around the country giving exhibitions through the late 1860s. Carolista typically performed as an entr’acte in a local gallery or theatre while Shaw attempted to drum up funds from the public for a more sensational open-air exhibition . Once a certain amount of money was raised, a date was picked, the rope was installed, and Carolista would go through her routine. Afterwards Shaw essentially passed a hat around in an attempt to solicit even more compensation from the excited crowds. Such was the format of their visit to Denver in July of 1861, as M’lle Carolista performed at the Criterion Saloon while Shaw circulated a subscription for a “Grand Tight Rope Ascension,” which eventually raised $170. A rope was stretched across Larimer Street from the New York Store to Graham’s Drug Store and on July 18, 1861, a large crowd gathered to witness M’lle Carolista’s daring feats. Ostensibly sensing an opportunity to cash in on the event, the Daily Republican and Rocky Mountain Herald reported that:

Mr. Wakely, Daguerrean and Ambrotypist on Larimer street showed us some beautiful views taken of the crowd assembled yesterday to see M’lle Carolista in her daring feat of rope walking. These are valuable not only on account of representing that interesting affair, but they also present a grand view of Larimer street, the pains, etc. Call at Wakely’s and see those pretty representations.

While the article suggests multiple views were made, the only extant version is the 4.25″ x 6.5″ half-plate ambrotype reproduced below.

By all accounts it was a very successful exhibition, and M’llle Carolista at one point balanced on the top of her head halfway across, amongst other dramatic variations. As the paper indicated, the ambrotype offers a beautiful view of Denver’s main thoroughfare, which is lined with newly built stores, including a confectionary and ice cream parlor. More entertainingly, a seemingly worried or flabbergasted man standing with his hands on his head can be seen in the center of the foreground.

At right is a detail of M’lle Carolista, who seems to have dressed up for the occasion, as she paused for Wakely’s photograph. This wonderful ambrotype offers both a tantalizing glimpse into the earliest era of Denver’s history and captures something of the vibrant world of mid-nineteenth century popular entertainment in the United States.

Sources: Peter E. Palmquist and Thomas R. Kailbourn, Pioneer Photographers of the Far West (2000); Terry Wm. Mangan, Colorado on Glass (1975); Melvin Schoberlin, From Candles to Footlights (1941)