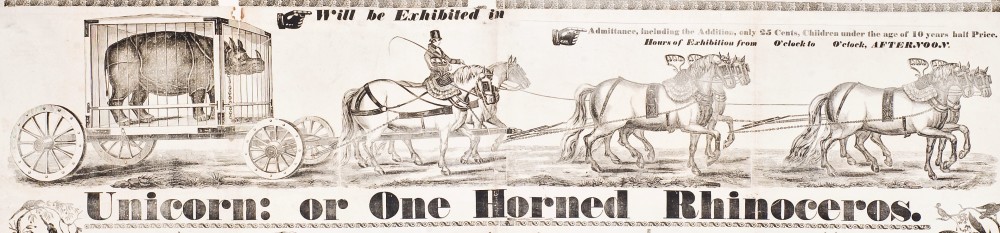

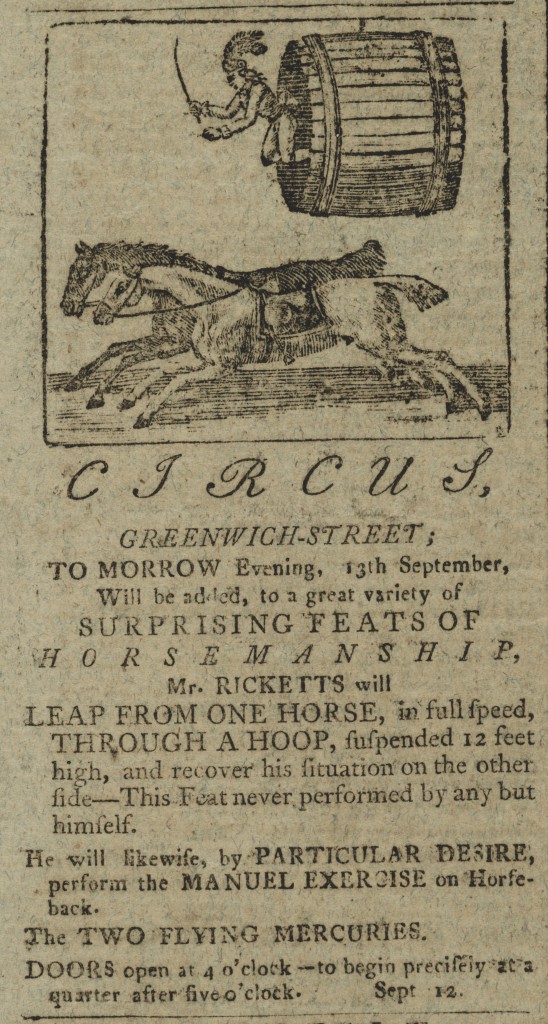

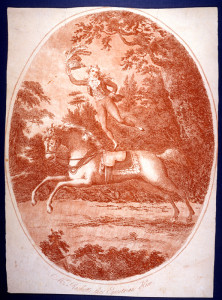

Although John Bill Ricketts was not the first equestrian performer to entertain American audiences, his combination of skill and enterprise has earned him deserved credit for establishing the circus as an enduring and popular form of entertainment in the United States. While the late-eighteenth century circus did include clowns and acrobats, it was centered on equestrian feats and riders like Ricketts were the stars of the show. Among the acts he was publicized as doing in New York City during his first tour were dancing a hornpipe on a “horse at full speed”; military exercises “in the character of an American officer,” complete with sword and firearms; “standing erect” on two horses without breaking “two eggs fastened to the bottom of his feet”; and various other skills on horseback, such as leaping through hoops, standing on his head, and performing somersaults while mounting and dismounting. The “Two Flying Mercuries” act advertised at left featured an apprentice who perched on Ricketts’s shoulders as the horse galloped around the ring, with both balancing on one foot for the finale.

After his April 1793 American debut, Ricketts spent the balance of the decade touring up and down the Eastern seaboard, until a disastrous fire at his Philadelphia amphitheatre in December 1799 effectively ended his career in the United States. Ricketts was widely admired in his day as both a performer and a gentleman, which helped ensure that the circus was seen as a respectable form of entertainment. The early chronicler American circus T. Alston Brown observed that:

John B. Ricketts, the proprietor, was a very gentlemanly and neat fellow in society and dressed in rather the English sporting style and was received with favor in the best circles. As a performer he never offended the eye by ungraceful postures or by the nude style of dressing that now prevails at the circus. His costumes were like that of the actors on the stage–pantalets, trunks full disposed, and neat cut jacket–which were sufficient to make ample display of his figure for all purposes of agility and grace.

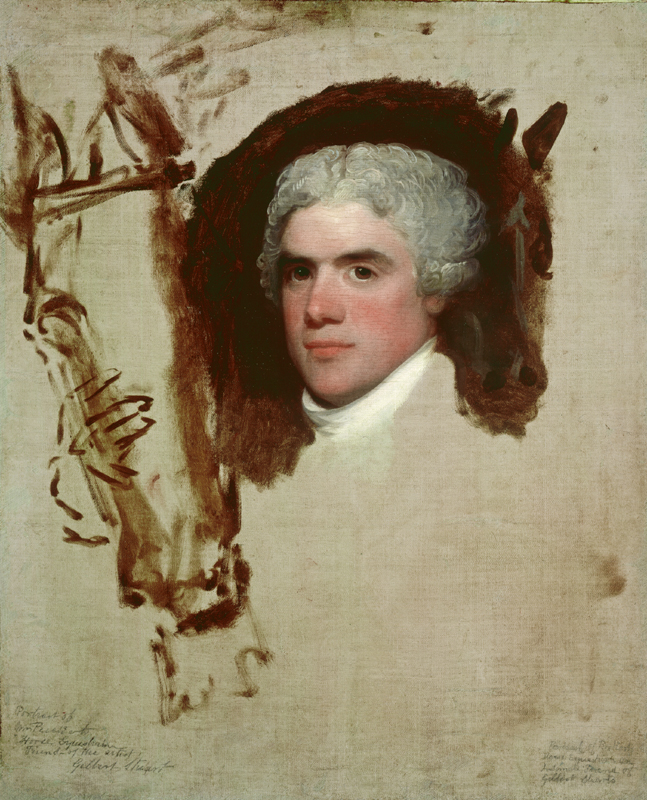

Indeed, his success was such that he sat for Gilbert Stuart, the foremost portraitist of the period. Although unfinished (supposedly due to his restlessness), the painting captures something of the pluck for which Ricketts was known.

The doings of Ricketts in the United States have been fairly well-documented, most notably in a dissertation by James Moy, and there are a variety of primary sources, from contemporary newspapers and ephemera to a wonderful memoir by the actor and dancer John Durang that chronicle his American years.

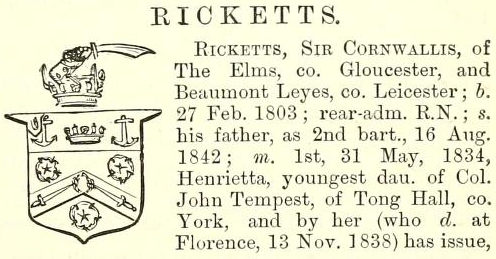

What has always been less clear about John Bill Ricketts is his life before and after his time in the United States. The availability of digitized historical newspapers and a recent find by Australian circus scholar Mark St. Leon has shed some new light on the former. It had generally been supposed that Ricketts was somehow associated with the line of Sir Cornwallis Ricketts of the Elms, Gloucester, owing to a bit of numismatic evidence. This is a token that was made at the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia for the circus in 1796, which bears the coat of arms very similar to that used by Sir Cornwallis (the addition of the anchors allude to his naval career).

What St. Leon has unearthed is a record for the christening of one “John Bill Ricketts” in the Parish registers of the town of Bilston in Staffordshire. The entry was made on October 28, 1769, and no parental names were listed, implying that the child was a foundling or otherwise illegitimate. The year certainly aligns with what we know of Ricketts’s career as that date would mean that he was around seventeen when he began performing at the Jones’ Equestrian Amphitheatre in London (1786) and twenty-four years old when he made his American debut (1793). Moreover, it was also very common for circus performers of that time to have been orphans. Of course this does not necessarily disprove some connection to the Ricketts who were part of the local landed gentry, but had he been a legitimate part of the family, a career as a circus performer would have been a very unusual career choice. I would suggest that his use of the coat of arms on the token was a case of him ‘putting on airs’ in the United States given what seem to be his humble origins. The Ricketts name was rather common, though, and there were prominent families with the surname living both England and the West Indies that seem to have used variations of this coat of arms.

Ricketts has also commonly been described as a Scotsman, and that is one thing that this record would seem to debunk. This mistaken assumption derived from the fact that he spent many of his formative years performing at the Royal Circus in Edinburgh. Presently, the first indication of him in the historical record seem to be digital newspapers that show a “Master Ricketts” or “Rickets” performing as a clown with Jones’ Equestrian Amphitheatre in April 1786. Where and when he received his training remains something of a mystery as seventeen would have been a rather old for a performer to make their debut. Ricketts told John Durang that he was a pupil of the famed equestrian and manager Charles Hughes, but his well-documented association with other circuses suggests that this might have been a bit of braggadocio, though still quite possible. Whatever the case, this finding does clear up something of his previously obscure origins.

The big remaining mystery is of course what happened to Ricketts towards the end of his life. After the fire and some desultory efforts to resurrect his circus in Philadelphia, Ricketts sailed for Barbados (where one George Poyntz Ricketts was coincidentally the colonial governor). The schooner Sally departed in May 1800 with ten horses and a small company of performers, but the ship was seized at sea by the French privateer Brilliante. A prize crew then sailed the ship to Pointe-à-Pitre in Guadeloupe. According to Durang, who did not accompany the party, but saw Francis Ricketts (John Bill’s brother) after he returned, an intervention by a sympathetic merchant allowed the troupe to recover its property and to begin performing. Francis is said to have both married and spent time in prison on Guadeloupe, but the circumstances of these events are murky.

Of John Bill Ricketts, Durang writes only that after performing for a length of time in Guadeloupe, he “sold all his horses to great advantage and had made an immense amount of money; he chartered an old vessel to take him to England; the vessel foundered and he was lost with all his money at sea.” The language of this passage makes it unclear from where Ricketts sailed. The seizure of the Sally created some controversy in Franco-American relations and generated a lawsuit, details of which ultimately ended up in the Congressional Record. These indicate that Ricketts had taken out a policy with the Insurance Co. of the State of Pennsylvania for four thousand dollars before sailing. Factoring in an abatement of two percent, the company eventually paid John Bill Ricketts $3,920, but it is unclear if he had to return to Philadelphia to collect. Although Francis Ricketts later performed in the United States, there is no definitive indication that John Bill Ricketts ever set foot there again. There was a “Mr. Ricketts” who performed with Langley’s circus in Charleston beginning in September 1800, ending with a benefit on January 8, 1801. Historian Stuart Thayer supposes this is Francis Ricketts, and I am inclined to agree, but this makes the timing of the Caribbean adventure and the subsequent activities of the brothers hard to reconcile. There are independent reports (Durang, Decastro) of John Bill Ricketts’s watery end, but I have yet to see anything about exactly where and when this might have occurred. If you have any information, please do let me know.

In his memoirs, Jacob Decastro, who had seen Ricketts perform firsthand in London during the late 1870s, remembered him as “the first rider of real eminence that had then appeared.” He went on to observe that the fame of Ricketts “excelled all his predecessors, and it is said he has never been surpassed.” Given his exalted status on both sides of the Atlantic and the pivotal role that this “Equestrian Hero” played in the development of the American circus, the fact that the mystery of how he met his end persists is somewhat surprising.

Sources: The manuscript of John Durang’s memoir is held by the Historical Society of York County, and it was published in 1966 as The Memoir of John Durang, American Actor, 1785-1816; T. Alston Brown wrote a serialized history of the American circus for the New York Clipper that was published as “A Complete History of the Amphitheatre and Circus from Its Earliest Date to 1861.” That text has been usefully edited and republished by William Slout as Amphitheatres and Circuses (Borgo Press, 1994); Kotar and Gesser, The Rise of the American Circus (2011); Stuart Thayer, Annals of the American Circus (2000); The Memoirs of J. Decastro, Comedian (1824).