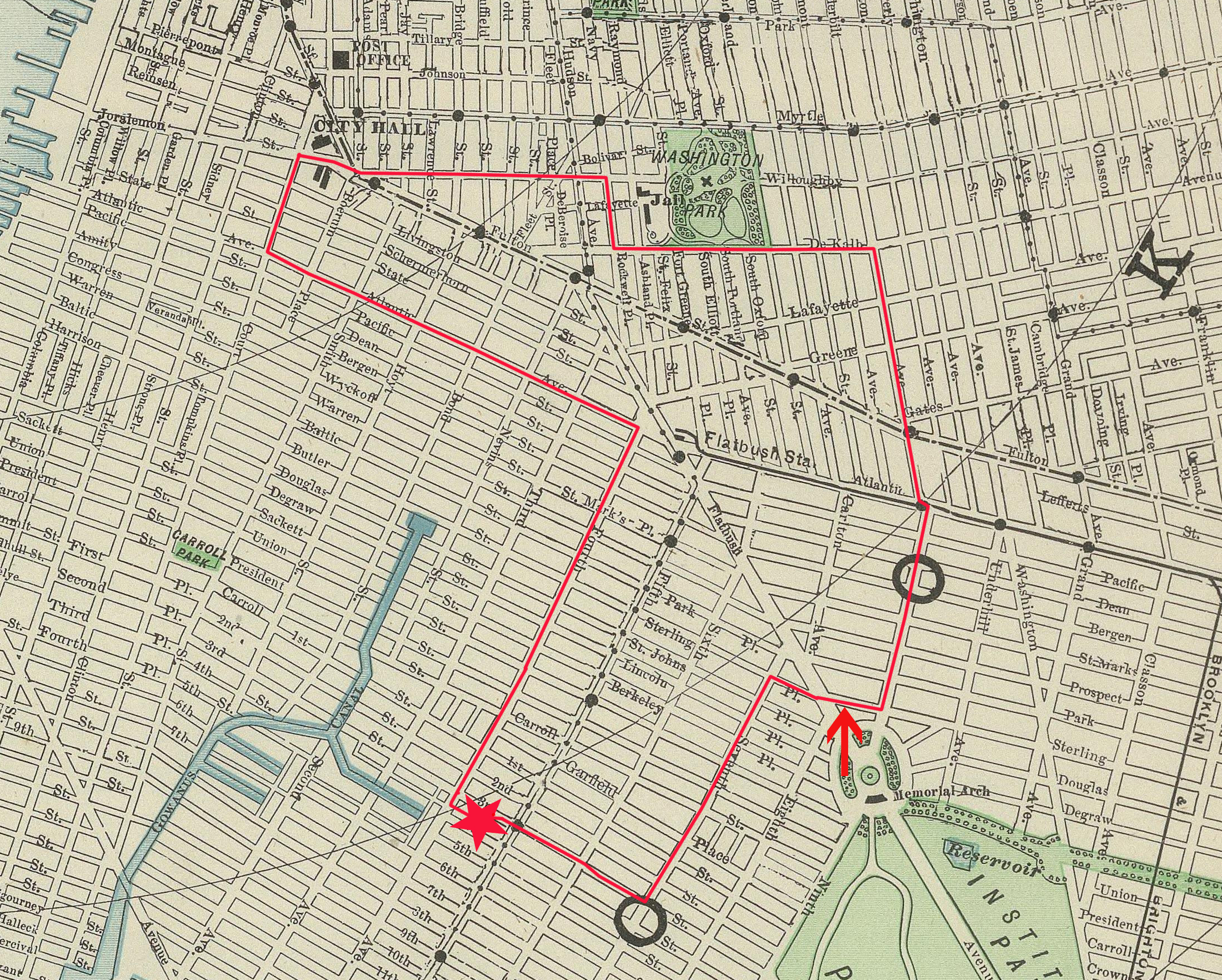

As the ‘Big Show‘ is back in Brooklyn today for the first time since the late 1930s, I wanted to throw up a quick post about the Ringling Bros. first visit to the borough. In late 1907, the Ringling brothers purchased the Barnum and Bailey Circus, and they ran the two circuses separately until 1919, when the combined Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus was formed. During the early twentieth century the winter quarters for the Ringling show were in Baraboo Wisconsin, and the circus typically opened in Chicago each season before heading out on tour. The Barnum & Bailey Circus on the other hand was based in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and would open its season at Madison Square Garden. In 1909, supposedly because Al had always dreamed of the Ringling circus conquering the Big Apple, they decided to switch things up and the Barnum & Bailey Circus was sent to Chicago, and the Ringling show made the 1100 mile trip to makes its New York City debut. They opened on March 25, and despite positive reviews, business was a bit slow during their month-long stand at the Garden. On Sunday, April 25, the circus moved to a lot at Fifth Avenue and Third Street in Brooklyn to prepare for the first show of the season under canvas, i.e., in a tent. Traffic and subway construction in Manhattan meant that circuses were no longer able to parade there. This was unfortunate because the 1909 Ringling parade is remembered by circus historians as perhaps the best that the brothers ever put together. On Monday morning at 9am, a procession that included 44 tableaux and cage wagons, a huge steam calliope, chariots drawn by horses, zebras and elephants, mounted riders, and a herd of twenty-two elephants, began its grand march through the streets of Brooklyn. A map of the route:

Courtesy David Rumsey Map Collection

When I was canvasing for materials for the Circus and the City exhibition, I stumbled across a box of photographic dry plates at the Somers Historical Society. The set of twelve plates depicted a circus parade and were produced by the Obrig Camera Co. of New York. Although labeled as “Barnum & Bailey,” when I looked at them on a lightbox it was plainly evident that they were actually Ringling Bros. wagons. After scanning the plates, the detective work began. Given the box was from Obrig, it seemed likely that the photographs were taken somewhere in New York City. And of course the only year that the Ringling show mounted a parade here was 1909. The seemingly characteristic Brooklyn brownstones in the background offered another clue, and I headed out to the Brooklyn Public Library to figure out the parade route, which the Brooklyn Daily Eagle duly provided. Luckily, the plate that featured Ringling’s famous Swan Bandwagon and its twenty-four-horse hitch gave a long view of the block, which included a rather distinctive cupola.

With the route and photographs in hand, I was hoping to be able to determine for certain when and where they were taken. Starting off from the old circus lot (where the Old Stone House now sits), I made my way through Park Slope and up to Flatbush Ave. via Sterling Place where, much to my delight, a promising cupola came into view. Walking a bit further east on Sterling Place made it clear that this was the right block. The plates were made by a photographer standing on the south side of Sterling Place looking west to the intersection with Flatbush Ave. on the morning of April 25, 1909 (see the red arrow on the map above). A few more slides from the series:

Here’s a picture I took from the approximate position of the original photographer. The block is obviously a lot greener today, but the north side of the street looks almost exactly like it did over a hundred years ago.

Although Brooklynites turned out to enjoy the parade and the headline verdict in the Eagle the next day was “Ringling Bros. Show Best Ever,” this was the only time that the Ringlings visited Brooklyn prior to the debut of the combined show. And while the parade has long gone by the wayside, it’s nice to see the Big Show back in Brooklyn again.