I have traded a view of this bridge:

For a view of this one:

Yes, those are ice floes….brrrrrr.

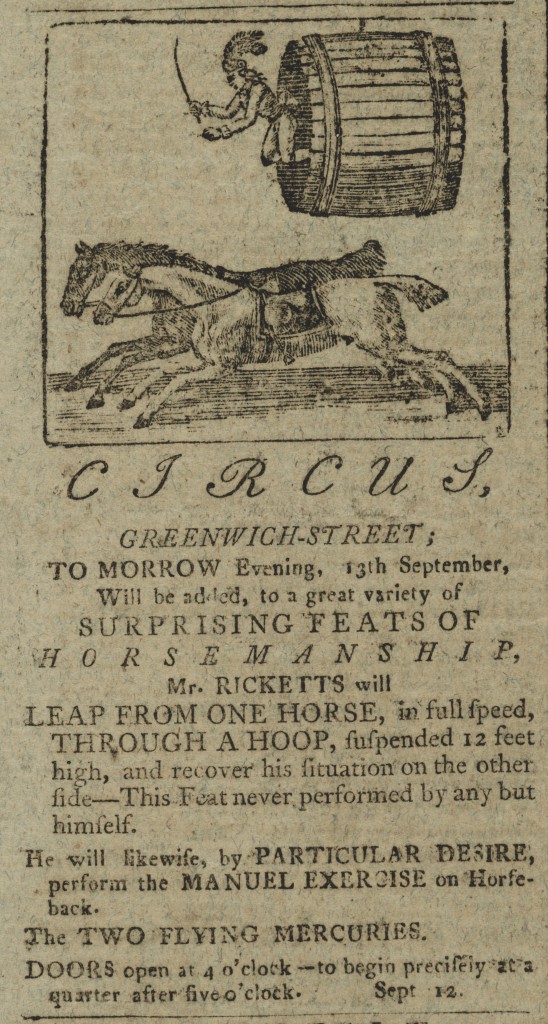

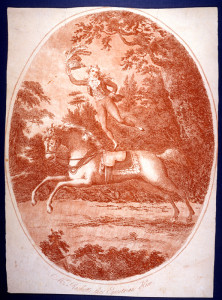

Although John Bill Ricketts was not the first equestrian performer to entertain American audiences, his combination of skill and enterprise has earned him deserved credit for establishing the circus as an enduring and popular form of entertainment in the United States. While the late-eighteenth century circus did include clowns and acrobats, it was centered on equestrian feats and riders like Ricketts were the stars of the show. Among the acts he was publicized as doing in New York City during his first tour were dancing a hornpipe on a “horse at full speed”; military exercises “in the character of an American officer,” complete with sword and firearms; “standing erect” on two horses without breaking “two eggs fastened to the bottom of his feet”; and various other skills on horseback, such as leaping through hoops, standing on his head, and performing somersaults while mounting and dismounting. The “Two Flying Mercuries” act advertised at left featured an apprentice who perched on Ricketts’s shoulders as the horse galloped around the ring, with both balancing on one foot for the finale.

After his April 1793 American debut, Ricketts spent the balance of the decade touring up and down the Eastern seaboard, until a disastrous fire at his Philadelphia amphitheatre in December 1799 effectively ended his career in the United States. Ricketts was widely admired in his day as both a performer and a gentleman, which helped ensure that the circus was seen as a respectable form of entertainment. The early chronicler American circus T. Alston Brown observed that:

John B. Ricketts, the proprietor, was a very gentlemanly and neat fellow in society and dressed in rather the English sporting style and was received with favor in the best circles. As a performer he never offended the eye by ungraceful postures or by the nude style of dressing that now prevails at the circus. His costumes were like that of the actors on the stage–pantalets, trunks full disposed, and neat cut jacket–which were sufficient to make ample display of his figure for all purposes of agility and grace.

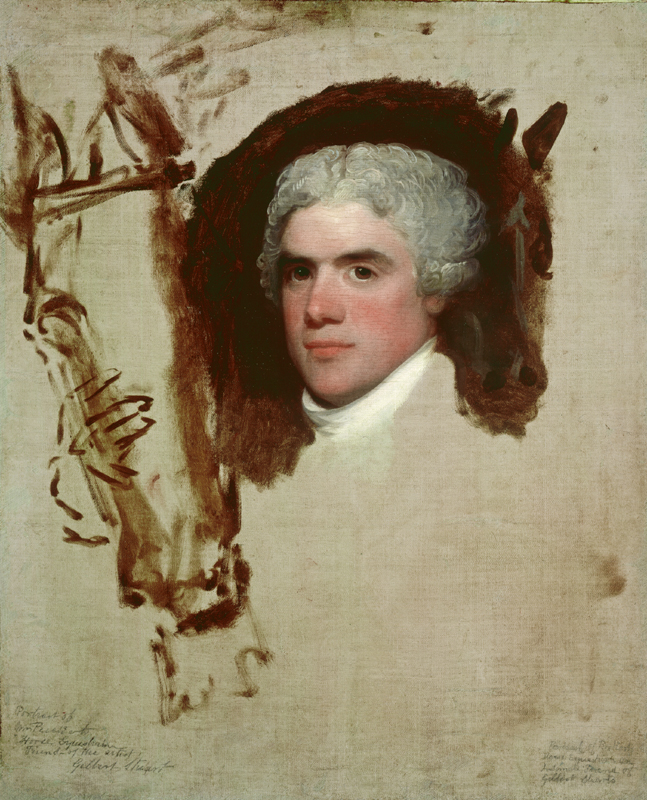

Indeed, his success was such that he sat for Gilbert Stuart, the foremost portraitist of the period. Although unfinished (supposedly due to his restlessness), the painting captures something of the pluck for which Ricketts was known.

The doings of Ricketts in the United States have been fairly well-documented, most notably in a dissertation by James Moy, and there are a variety of primary sources, from contemporary newspapers and ephemera to a wonderful memoir by the actor and dancer John Durang that chronicle his American years.

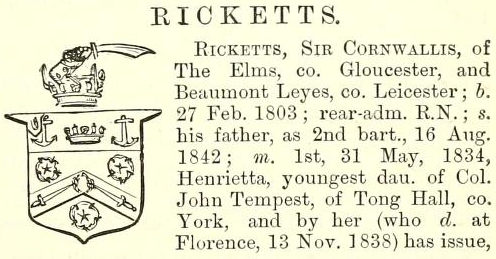

What has always been less clear about John Bill Ricketts is his life before and after his time in the United States. The availability of digitized historical newspapers and a recent find by Australian circus scholar Mark St. Leon has shed some new light on the former. It had generally been supposed that Ricketts was somehow associated with the line of Sir Cornwallis Ricketts of the Elms, Gloucester, owing to a bit of numismatic evidence. This is a token that was made at the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia for the circus in 1796, which bears the coat of arms very similar to that used by Sir Cornwallis (the addition of the anchors allude to his naval career).

What St. Leon has unearthed is a record for the christening of one “John Bill Ricketts” in the Parish registers of the town of Bilston in Staffordshire. The entry was made on October 28, 1769, and no parental names were listed, implying that the child was a foundling or otherwise illegitimate. The year certainly aligns with what we know of Ricketts’s career as that date would mean that he was around seventeen when he began performing at the Jones’ Equestrian Amphitheatre in London (1786) and twenty-four years old when he made his American debut (1793). Moreover, it was also very common for circus performers of that time to have been orphans. Of course this does not necessarily disprove some connection to the Ricketts who were part of the local landed gentry, but had he been a legitimate part of the family, a career as a circus performer would have been a very unusual career choice. I would suggest that his use of the coat of arms on the token was a case of him ‘putting on airs’ in the United States given what seem to be his humble origins. The Ricketts name was rather common, though, and there were prominent families with the surname living both England and the West Indies that seem to have used variations of this coat of arms.

Ricketts has also commonly been described as a Scotsman, and that is one thing that this record would seem to debunk. This mistaken assumption derived from the fact that he spent many of his formative years performing at the Royal Circus in Edinburgh. Presently, the first indication of him in the historical record seem to be digital newspapers that show a “Master Ricketts” or “Rickets” performing as a clown with Jones’ Equestrian Amphitheatre in April 1786. Where and when he received his training remains something of a mystery as seventeen would have been a rather old for a performer to make their debut. Ricketts told John Durang that he was a pupil of the famed equestrian and manager Charles Hughes, but his well-documented association with other circuses suggests that this might have been a bit of braggadocio, though still quite possible. Whatever the case, this finding does clear up something of his previously obscure origins.

The big remaining mystery is of course what happened to Ricketts towards the end of his life. After the fire and some desultory efforts to resurrect his circus in Philadelphia, Ricketts sailed for Barbados (where one George Poyntz Ricketts was coincidentally the colonial governor). The schooner Sally departed in May 1800 with ten horses and a small company of performers, but the ship was seized at sea by the French privateer Brilliante. A prize crew then sailed the ship to Pointe-à-Pitre in Guadeloupe. According to Durang, who did not accompany the party, but saw Francis Ricketts (John Bill’s brother) after he returned, an intervention by a sympathetic merchant allowed the troupe to recover its property and to begin performing. Francis is said to have both married and spent time in prison on Guadeloupe, but the circumstances of these events are murky.

Of John Bill Ricketts, Durang writes only that after performing for a length of time in Guadeloupe, he “sold all his horses to great advantage and had made an immense amount of money; he chartered an old vessel to take him to England; the vessel foundered and he was lost with all his money at sea.” The language of this passage makes it unclear from where Ricketts sailed. The seizure of the Sally created some controversy in Franco-American relations and generated a lawsuit, details of which ultimately ended up in the Congressional Record. These indicate that Ricketts had taken out a policy with the Insurance Co. of the State of Pennsylvania for four thousand dollars before sailing. Factoring in an abatement of two percent, the company eventually paid John Bill Ricketts $3,920, but it is unclear if he had to return to Philadelphia to collect. Although Francis Ricketts later performed in the United States, there is no definitive indication that John Bill Ricketts ever set foot there again. There was a “Mr. Ricketts” who performed with Langley’s circus in Charleston beginning in September 1800, ending with a benefit on January 8, 1801. Historian Stuart Thayer supposes this is Francis Ricketts, and I am inclined to agree, but this makes the timing of the Caribbean adventure and the subsequent activities of the brothers hard to reconcile. There are independent reports (Durang, Decastro) of John Bill Ricketts’s watery end, but I have yet to see anything about exactly where and when this might have occurred. If you have any information, please do let me know.

In his memoirs, Jacob Decastro, who had seen Ricketts perform firsthand in London during the late 1870s, remembered him as “the first rider of real eminence that had then appeared.” He went on to observe that the fame of Ricketts “excelled all his predecessors, and it is said he has never been surpassed.” Given his exalted status on both sides of the Atlantic and the pivotal role that this “Equestrian Hero” played in the development of the American circus, the fact that the mystery of how he met his end persists is somewhat surprising.

Sources: The manuscript of John Durang’s memoir is held by the Historical Society of York County, and it was published in 1966 as The Memoir of John Durang, American Actor, 1785-1816; T. Alston Brown wrote a serialized history of the American circus for the New York Clipper that was published as “A Complete History of the Amphitheatre and Circus from Its Earliest Date to 1861.” That text has been usefully edited and republished by William Slout as Amphitheatres and Circuses (Borgo Press, 1994); Kotar and Gesser, The Rise of the American Circus (2011); Stuart Thayer, Annals of the American Circus (2000); The Memoirs of J. Decastro, Comedian (1824).

Later this week I will be giving a talk for a digital history symposium at the University of Newcastle on the subject of “Mapping Cultural Circuits.” Some of my work in this vein can be found under the Mapping subheading on this website, but I will be presenting a more complete view of historical GIS maps that chart the development of a Pacific entertainment circuit in the nineteenth century at the symposium. This information has unfortunately become rather difficult to display in a public-facing website as Google neglected to update the gadgets used to embed KML layers from Google Earth when it transitioned to the new maps API. So I have instead produced a short video that uses Google Earth and some rectified historical maps to trace the grand tour around the world undertaken by the General Tom Thumb Company from 1869 to 1872. The video highlights some of what I find most useful about using this combination of tools to visualize the history of transnational touring circuits.

The new Google Maps API does have some salutary features, one of which is the ability to create ‘heatmaps’ of data. The image below is a screenshot of the aggregate data from the touring routes of some three dozen American shows and entertainers that toured the Pacific between 1850 and 1890.

The visualization shows that Melbourne, which grew into one of the largest and wealthiest cities in the Pacific over the course of the nineteenth century, was the primary destination for American entertainers during this period. And while the cultural traffic between San Francisco and Melbourne was the primary axis of the emergent Pacific circuit, there are also indications of other noteworthy features, ranging from the importance of Honolulu as a kind of transpacific relay station to the somewhat surprising prominence of the Dutch East Indies. All of this will obviously be expounded upon in the talk, but for those that can’t make it, check back for updates as I will be posting more of this mapping material on the webiste in the coming months.

I was at the ABC Radio complex yesterday for an interview with the peerless Margaret Throsby. We talked a lot about the circus, a bit about entertainment around the Pacific, and even squeezed in some discussion of numismatics. All in all I had a wonderful time and our conversation can be found in podcast form here.

One of the things that I am packing up for the move across country is a fine print that I acquired at a garage sale here in Cheesman Park. It is an 1845 aquatint of a trotting horse named Lord William and a delightful example of the widely popular British sporting prints that were produced during the mid-nineteenth century. According to Bent’s Register of Engravings (1846), it was engraved and published in London by J. R. Mackrell after a painting by William Shayer. Prices are listed for both a plain (7s 6d) and colored edition (15s). After a bit of haggling, I paid $20 for this plain version, which I think actually looks better than the color print.

William Joseph Shayer (1811-1892) was an English artist and the eldest son of William Shayer (1787-1879), a noted landscape and figure painter from Hampshire. The younger Shayer specialized in coaching and hunting scenes, but as both signed their works “W.S.” and painted in the same style, there is often some confusion with regards to the attribution of their respective works. Given the subject and date, it seems clear that this particular print was based on an early work by the younger Shayer (and if a reader can point me to the original painting, do let me know). The painting below, descriptively entitled The London to Brighton Stage Coach (ca. 1850), offers a good impression of his typical subject matter and technique.

The pleasing pastoral and sporting scenes painted by the Shayer family made their works popular with printmakers who sought to capitalize on the seemingly insatiable public demand for such images. Hundreds, if not thousands, of different prints after the Shayers’ works were produced in volume in London and beyond during the nineteenth century.

The “Lord William” aquatint was made by a prolific engraver named James R. Mackrell (ca. 1814-1866). As previously noted it was first published in 1845, but some restrikes seem to have been made at a later date. An aquatint is a variety of etching that was invented in France in the 1760s, and its characteristic feature is to give the appearance of watercolor washes. The process involves a copper or zinc plate that is covered with powdered rosin and then progressively etched and bathed in acid to create the desired lines and tonal variations. An intaglio method of printmaking, the resulting incised image is able to hold ink and is then passed through a press with a sheet of paper to produce the final print. The appeal of the aquatint was that it provided printers with a way to more easily create large areas of tone, and the durability of the plates used allowed for large print runs. The distinctive “watery” look of the aquatint proved popular with the public as well, and even after the ascent of lithography in the mid-nineteenth century, aquatints were still being produced in large numbers.

I was initially under the impression that the titular “Lord William” was the driver, and it was only upon closer inspection that I realized that it was the horse. The descriptive text underneath the image indicates that he was the property of one Samuel Lawrence, Esqr., while also noting the following: ‘This Extraordinary animal Trotted a Match against time in harness, for a wager of 200 Sovereigns aside from London to Brighton in the unprecedented time of Three hours and Fifty minutes. October 14th 1842. Driven by the Owner.’ Harness racing, in which horses race at a specified gait pulling a wheeled cart called a sulky, had originated in North American in the late 17th century and the first recorded harness races in Britain were held in 1750. By the mid-nineteenth century, it was a favored form of sport and gambling among gentlemen of means, as the relatively large stakes of this contest suggest. Although races are now held at formal tracks, at the time they were usually staged as single matches between two gentlemen and their steeds over a proscribed road and/or distance. The famed Brighton Road (the modern day A23) was fifty-one and a half miles as measured from the south side of Westminster bridge to the seaside aquarium in Brighton, which was then a fashionable resort. Horses bred specifically for trotting came to be known as “Standardbreds” because they had to be able to trot a “standard” mile in less than two and a half minutes. In his race from London to Brighton, Lord William traveled at a clip of 13.4 miles per hour or a little less than four and a half minutes per mile, an impressive pace given the total distance. Unfortunately, I have been unable to locate a contemporary account of the contest, so this print might serve as the only record of Lord William’s victory.

Sources: Brian Stewart and Mervyn Cutten, The Shayer Family of Painters (1981); Wray Vamplew, The Turf: A Social and Economic History of Horse Racing (1976); for a more recent and entertaining account of horse racing in New York see Steven Reiss, The Sport of Kings and the Kings of Crime (2011)

Opinion column for the New York Daily News, published February 16, 2014.

The times are changing.

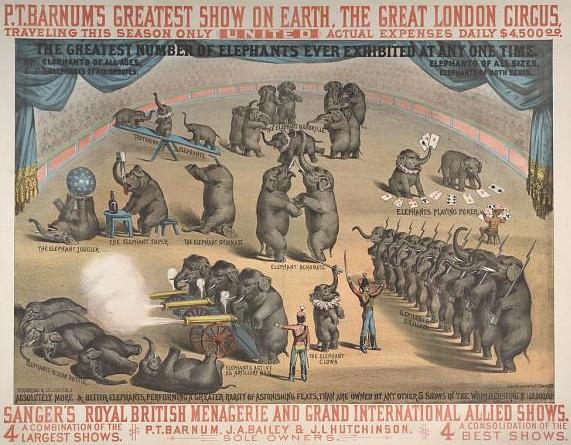

The arrival this week of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus at Barclays Center has prompted a renewed push by animal welfare advocates for the city to ban wild or exotic animals like elephants and lions in public entertainments.

Having studied the history of circuses nationally and in New York, and understanding the evolution of this particularly American spectacle, I support the ban — not because I loathe the circus, but because I know it intimately and, for the most part, love it.

The City Council has previously proposed bills that would have effectively prohibited circuses from using exotic animals in their New York shows — and momentum seems to be building for a ban now. Animal rights groups like NYCLASS, which has been instrumental in the effort to end the use of carriage horses in Central Park, have undoubtedly been emboldened by Mayor de Blasio and Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito’s past support of such legislation and the broadening public concern for animal welfare.

The Ringling show and other American circuses that employ more traditional big cat acts and performing elephants are of course adamantly opposed, insisting that their animals are well cared for and offer audiences a unique blend of education and entertainment.

Those who protest the circus outside of Barclays or grimace as they take their children inside the arena despite the signs need to understand the historical context.

This debate over the use of animals in popular entertainment is a long-running one, extending back to at least the late 18th century, when exotic-animal exhibitions flourished and the acrobat and rider John Bill Ricketts established the first circus in New York City. In the decades that followed, traveling shows featuring a panoply of daring performances and wild animals became so numerous and popular that Walt Whitman declared the circus “a national institution.”

The circus was not immune from controversy or criticism, with much of the opposition rooted in religiously motivated concerns about the perceived immorality of the performers and the treatment of the animals. Isaac Van Amburgh found fame and fortune in the 1830s by becoming the first trainer to enter the cages and perform with the lions and tigers, the so-called big cats. While many found his performances thrilling, others were horrified by their brutality as Van Amburgh regularly thrashed his animal charges with a metal bar in the course of the act.

Opposition to the circus was ultimately ineffectual, and by the late 19th century it was perhaps Americans’ favored form of entertainment, with hundreds of traveling shows of all sizes crisscrossing the country every year.

And yet sporadic debates over the treatment of animals persisted, particularly in New York City, where the founding of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals by Henry Bergh coincided with the rise of P. T. Barnum’s celebrated circus.

Bergh and Barnum fought a series of battles, most notably in 1880 over an act by a horse called Salamander that jumped through flaming hoops and fireworks. But the occasional controversy only seemed to draw more people in.

Incidents such as the 1902 public execution by choking of an unruly Barnum & Bailey elephant named Mandarin along the city docks provoked an outcry, but it was not until the 1920s that organized activist pressure led John Ringling and other circus owners to begin dropping or altering acts that suggested cruelty.

And so, the sharp disagreements and protests occasioned in more recent years by the annual visit of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus to the New York area are just the latest iteration of a long-running struggle. What’s different — and ironic — is that, despite undeniable improvements in the conditions of many of the animals, advocates for animal welfare finally seem to be winning the argument.

That the venerable Big Apple Circus now almost exclusively employs domestic animals like dogs and horses is a good indication of this trend, as is the near-absence of animals in Cirque du Soleil, Circus Oz and other circus-inspired shows that frequent the city.

Increasing public concern about animal welfare has arguably led American circuses to institute some constructive changes in their treatment of animals. But the massive fine the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus paid to the USDA in 2011 for violations of the Animal Welfare Act suggests that serious issues persist.

Moreover, the fact is that many people, myself included, believe that wild animal acts are outmoded and often cruel. We find the sight of circus elephants being put through their paces — beautiful, large and intelligent creatures compelled to perform silly acts to cheering crowds — troubling.

My own opposition is rooted in a moral conviction that the dignity and well-being of wild animals is fundamentally at odds with forcing them to perform for our entertainment. Whatever its source, it is a feeling that is widely shared, as bans on the use of circus animals are being implemented the world over, with India and the United Kingdom among the most recent to adopt prohibitions.

You need only witness the intense, passionate reaction to Blackfish, the documentary story of Seaworld’s killer whale Tilukum, to understand that a new moral imperative is spreading in the air, and the water.

Public relations efforts and appeals to tradition by defenders of the circus cannot shield from scrutiny practices that so many people in this city and around the world now find inhumane. The standards for what constitutes animal welfare for mainstream Americans have and will continue to evolve, but a serious reconsideration of using wild animals in the service of commercial entertainment is clearly underway — and the prospective ban on exotic and wild animals in New York City is part of this process.

As a circus fan and historian, I can only hope that the holdouts grasp this ongoing shift and abandon the use of wild animals in favor of the spirit of innovation that allowed the American circus to flourish in the first place.

If they do not, then it is high time for animal welfare advocates and their allies at City Hall to act.

One of the things that I referred to in the op-ed I had published over the weekend was the public execution of the elephant Mandarin, which occurred in November 1902. It happened shortly after the Barnum & Bailey Circus arrived aboard the S.S. Minneapolis, docking at Pier 40 on Manhattan’s west side. The circus had been on an extended tour through Europe, and just before departing London, Mandarin struck and killed a keeper with his trunk. He was unruly throughout the crossing, and owner James Bailey decided to have him killed rather than risk Mandarin killing or injuring another worker or the other animals. When the circus steamed into New York Harbor, the Evening World sensationally reported that there was a “MAD ELEPHANT” rampaging onboard and helpfully provided a sketch of the ship for readers.

Four years earlier, the circus had departed for Europe with a herd of eighteen elephants. A photograph on Buckles Blog shows the herd of ten large and eight small elephants. Six of them, including all four big males, died during the tour.

George Conklin (1845-1924) was a lion tamer and elephant trainer who served as the “Superintendent of Animals” for the Barnum & Bailey Circus while it was abroad. His memoir as recorded by journalist Harvey W. Root was published by Harper & Row in 1921 as The Ways of the Circus: Being the Memories and of George Conklin Tamer of Lions. Conklin believed that choking was the “easiest and most humane” way to put down an elephant. In his account of the tour, he describes how a rope and block system was first used to kill Don Pedro at Liverpool in May 1898 after he became aggressive. On the last day of that initial touring season at Stoke-on-Trent, another male Asian elephant named Nick was strangled after becoming unruly. The largest of the elephants, Fritz, was killed after going on a rampage in Tours, France. It was only with much luck that Conklin was able to get him chained to a tree, and a hundred men pulled for fifteen minutes before he was finally choked to death. Fritz’s body was donated to the Musee de Beaux Arts, where it is still on display today.

Last but not least was of course Mandarin. Conklin’s rather laconic account of the killing of the elephant is as follows:

Mandarin was about forty-five years old, all of eight feet high, and heavy in proportion. We brought him to New York in a big crate on the upper deck of the boat. On the way over, Mr. Bailey decided to have him killed, so instead of unloading him on to the pier, Mr. Bailey had a big seagoing tug come alongside, and the crate, elephant and all, was swung down to the deck of the tug, which then put out to sea. When far enough outside the crate was loaded down with pig iron, swung out over the water, and let go. And so ended Mandarin (131).

The New York Tribune, on the other hand, provided a much more sensational account of the proceedings in its November 9 edition. Mandarin, with “head cased in leather harnesses,” and “trunk and legs manacled with huge chains,” was slowly strangled to death on the deck of the ship using a two-inch thick hawser (rope) and windlass. The article also suggests why Conklin’s account was terse, observing that: “George Conklin, the trainer, who had made an especial pet of Mandarin, could not witness the elephant’s end. He watched the preparations, but just before the time for the execution burst into tears and ran away.” A crowd of spectators watched from the docks as the elephant was choked to death; it took about eight minutes and seemed “painless” to the reporter on hand. The next morning Mandarin’s body was disemboweled on deck with “his comrades trumpeting the while,” and then loaded onto another ship, weighted down with lead, and dumped out at sea.

Though less infamous than the electrocution of Topsy at Coney Island or the hanging of the elephant Mary in Kingsport, Tennessee, Mandarin’s execution was an instructive example of the way that the contemporary circus industry valued profits over the welfare of its animals. But part of what makes “The Elephant People” chapter of Conklin’s book so fascinating is that he so clearly cares for the elephants, even as he describes doing things that most modern observers would undoubtedly find troubling. Ideas about what constitutes the humane treatment of animals have simply changed over the last century, and this is what has made the use (and abuse) of wild animals in commercial entertainment increasingly problematic.

It took over half a century for elephants to become integrated into the circus in the United States, and it was not until the late nineteenth century that herds of performing elephants like the one advertised above became common (for a penetrating historical analysis of this process, see Susan Nance’s Entertaining Elephants: Animal Agency and the Business of the American Circus). As the fortunes of the circus in the United States declined over the course of the twentieth century, so did the use of elephants, and the circus revival of recent decades has been driven almost exclusively by shows that have abandoned traditional wild animal acts. Clearly something akin to the public execution of Mandarin is unlikely to happen today, and the episode serves as an apt illustration of the way ideas about animal welfare in the United States have evolved. Now it is up to the American circus industry to fully catch up.

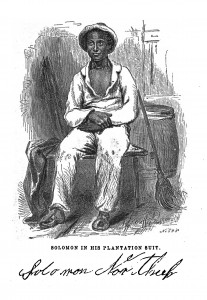

This past weekend I was finally able to see 12 Years Slave, which has been one of the most talked about and lauded films of the past year. Given the rather harrowing subject matter, it was not necessarily something I was looking forward to, but I came away impressed with the film as both a work of art and a powerful consideration of the historical legacy of slavery in the United States. As most readers will undoubtedly already know, it is based upon the experiences of Solomon Northrup, a free-born African American from upstate New York, who was kidnapped and sold into slavery in 1841. After over a decade working on different plantations in Louisiana, Northrup was able to secure his freedom with the help of an itinerant Canadian carpenter and friends from the North. Working with an editor named David Wilson, Northrup subsequently published a narrative of these events entitled Twelve Years a Slave (originally published in 1853, link is to an 1859 edition). Although there is some scholarly debate about the veracity of all the happenings and anecdotes included therein, it is unquestionably a powerful account of the American slavery system.

John Ridley’s admirably spare adaption for the most part remains faithful to Northrup’s narrative, and the episodic fashion in which Steve McQueen’s film unfolds was, I thought, particularly effective. In short, I liked it because it does not try to do too much. I am not sure what I can contribute to the already voluminous and penetrating commentary on the film (see this great piece by Wesley Morris for one), but I had a few thoughts that I wanted to share. For one, it was simply refreshing to see an honest depiction of slavery in American popular culture. The racial power dynamics portrayed in the film long outlasted slavery, and the nation’s tortured race relations have been reflected and refracted in American culture in ways that typically marginalize black people and experiences or turn them into a form of entertainment for white audiences. In presenting the brutal historical legacy of slavery from a black perspective, 12 Years a Slave powerfully confronts the pernicious cultural legacy that haunts American popular culture. One of the more striking scenes in the film for me was when the drunken Master Epps rouses Solomon and the other slaves from their quarters late one night to dance for his amusement. Finding their enthusiasm wanting, an enraged Epps screams at the “damned niggers,” whip in hand, until sufficient spirit is shown and he begins to cavort with his “property.” The dismal scene is arguably an apt metaphor for the traditional dynamics of popular entertainment in the United States.

While I certainly found the film and its implications disturbing, it was not as hard to watch as I expected. Part of this was no doubt due to my knowledge about the history of slavery going in, but it was also due to McQueen’s masterful direction. Despite telling a relatively straightforward and downright brutal story, the film is not unrelenting. At times the camera lingers on the natural beauty of a scene; at others we see some of the small triumphs of Solomon and the other slaves in their struggle to preserve their humanity. Probably the most cutting scenes for me were those in the New Orleans slave market, where we see the dehumanizing process of chattel slavery at work (for a great scholarly take on the same, see Walter Johnson’s Soul by Soul). The one scene that fell a bit flat for me, and one which I appreciate was supposed to be a very emotional moment, was Solomon’s singing of “Roll Jordan Roll” at the funeral of an unnamed fellow slave. Spirituals, and music more generally, clearly played an important role in slave life (see Shane and Graham White’s The Sounds of Slavery), but the use of this particular song in what was ostensibly a transformative moment just felt a bit contrived to me. I could probably write an entire book on the role of music and dancing in the film, though, so it is perhaps best to move along.

This might sound strange, but the work that resonated most with me in thinking about this film was James Agee and Walker Evans’ Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941). Although McQueen is trying to represent something of the historical reality of slavery and Agee/Evans are considering the contemporary lives of white sharecroppers amidst the Great Depression, both are works of art that center on somehow capturing and communicating the humanity of their subjects. This probably deserves a much longer post and explanation, but I cannot help but think of the two as complementary. In the “Preamble” to Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Agee struggles with the limits of representation and human experience, writing that “a piece of the body torn out by the roots might be more to the point” than a “book,” and he goes on to warn the reader that if they were to truly understand what he wants to communicate, “you would hardly bear to live.” I imagine that McQueen likewise struggled with these issues, albeit in a rather different context. I also cannot help but think that Agee would have appreciated the naturalism, economy of style, and moral force of 12 Years a Slave. There’s a powerful moment in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (“Late Sunday Morning”) when a group of African-American singers perform for Agee and Evans at the behest of their white landlord, much to the discomfort of both parties. The scene eerily echoes Epps forcing his slaves to dance, though in this case Agee is “sick in the knowledge that they felt they were here at our demand, mine and Walker’s, and that I could communicate nothing otherwise.” Though much had obviously changed in the intervening century, the stultifying racial power dynamics remain, and a disconcerted Agee plays his part through by tipping the young men, who thank him in a “dead voice” and go on their way. Agee and McQueen each in their own way grapple with the discomfitting history of American race relations, and their respective works of art succeed in part because they are so clearly moral efforts. In 12 Years a Slave, McQueen has produced an at once beautiful and harrowing film that forthrightly addresses the terrible history and complex cultural legacy of slavery in the United States. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

*A quick final note, and one that some will no doubt find superfluous. Solomon Northrup was lured from Saratoga Springs to Washington by two men, Brown and Hamilton, who promised him work with a circus company there. Brown was apparently a small-time magician and ventriloquist as he performed a show in Albany for an audience that Northrup recalled was “not of the selectest of character.” They arrived in Washington in early April and a quick check of the relevant sources shows that that there was no circus wintering there and a touring show did not arrive until later that summer. It thus seems clear then that neither Brown nor Hamilton were actually affiliated with a circus and this was simply a ruse to lure Northrup south. While the nineteenth-century American circus undoubtedly had its share of dodgy characters, skipping out on debts was more par for the course. Still, the deception does reinforce why itinerant entertainers were looked on with such suspicion by so many Americans at the time.

Further reading: Solomon Northrup, Twelve Years a Slave (1853); Clifford Brown, et. al., Solomon Northup: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years a Slave (2013); Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (2001); Shane and Graham White, The Sounds of Slavery (2005); James Agee and Walker Evans, Let us now Praise Famous Men (1941); Laurence Bergreen, James Agee: A Life (1984).

Above is a large-format photograph of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus performing at the Bronx Coliseum in March 1929 that I recently acquired at an auction. It was taken by Edward J. Kelty (1888–1967), who has been described as the “Cecil B. DeMille of circus photography” for the spectacular series of oversize prints he made using a custom-built banquet camera in the 1920s and 1930s. The photograph is of the so-called grand entrée when the circus performers and animals paraded around the ring in spectacular costume to open the show. The 1929 Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus was notable for being the last of the lavish editions of the show produced prior to the stock market crash that plunged the United States (and the circus industry) into depression. The circus was also unique for the fact that instead of beginning the season at Madison Square Garden, it began in the Bronx to celebrate the public opening of what was then called the New York Coliseum. The building was originally constructed as an auditorium for Philadelphia’s 1926 Sesquicentennial Exposition, and it was subsequently purchased by Edward B. Whitewell, owner of the Starlight Amusement Park, which was a kind of Bronx version of Coney Island that flourished in the 1920s. The arena was reconstructed at Bronx River and 177th Street with a Romanesque facade and seating for around 15,000. The March 21st opening of the building was celebrated by ex-Governor Al Smith and other dignitaries, although the photo above seems to be from a later daytime performance by the Ringling show. The stars of the circus were Goliath, billed as “The Monster Sea Elephant,” and Hugo Zacchini, an Italian daredevil who sensationally reintroduced the “human cannonball” act to the American circus. After a successful week in the Bronx, the circus transferred to Madison Square Garden for the remainder of its New York run. Despite its glittering debut, the New York Coliseum was not very successful as a venue, although it hosted everything from boxing matches to midget auto racing before being repurposed by the U.S. Army as vehicle-maintenance center during World War II. It was subsequently taken over by the New York City Transit Authority, and the building is now known as the West Farms Bus Depot.

A massive collection of Kelty photographs is available via the Ringling Museum here. For further information, see Step Right this Way: The Photographs of Edward J. Kelty and my own Circus and the City catalogue. All information about the history of the Bronx Coliseum is from a “Streetscapes” column by the peerless Christopher Gray in the New York Times.

*A reader noted that there is a Kelty photograph in Josh Sapan’s neat new book The Big Picture: America in Panorama

The centennial of the International Exhibition of Modern Art, better know as simply the Armory Show, has prompted a renewed wave of interest and a number of competing exhibitions about what many regard as the most important event in the history of American art. A full list of exhibitions and related publications can be found here, but perhaps the most prominent of these shows is the New-York Historical Society’s Armory Show at 100, which runs through February 23, 2014. I had the opportunity to visit when I was in New York City last week, and I must say that I came away rather disappointed (though the accompanying website is useful). Although the NYHS was able to get some fantastic material on loan for the exhibition, the overall interpretation was creaky and its organization was at times simply confusing.

First and foremost, it is not clear where the exhibition actually starts, with a small gallery of material about “Organizing the Armory Show” and a hallway full of contextual information about New York City in the early twentieth-century awkwardly positioned before the main gallery (I am still not sure if I was meant to go through these before or after the art). Whatever the case, the central gallery includes some 100 works drawn from over thirteen hundred pieces that appeared in the 1913 exhibition. One thing that is made very clear from the beginning is the overall theme, which promises “Modern Art & Revolution,” but much of what follows belies this bold promise and the conflation of politics and aesthetics is problematic throughout. The NYHS exhibition is roughly structured along the same lines as the original show, but the very truncated wall texts deal in such generalities that it is sometimes difficult to get a strong sense of either the historical exhibition or the contemporary interpretation being proposed.

One salutary feature of the present exhibition is its fidelity to representing the wide range of art works that appeared in the Armory Show, much of which was neither revolutionary nor particularly modern. The American painter Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917) and French Symbolist Odilon Redon (18401-1916) were among the most well-represented and received artists, and neither are particularly well-known today.

My favorite paintings in the exhibition (and it is almost entirely paintings) were those by what I would call the American avant-garde. George Bellows’ The Circus, Robert Henri’s Figure in Motion, Arthur B. Davies’ Line of Mountains, and John Sloan’s McSorley’s Bar are all wonderful paintings by artists identified with the so-called Ashcan School. All of these artists were also “revolutionary” and “modern” in their own way, but the framing of the exhibition is so narrowly focused on celebrating an ostensibly sui generis European modernism that it effectively marginalizes innovative American art. Indeed, this was something that many American artists bemoaned about the the Armory Show at the time, so I suppose it is only proper that this current exhibition similarly elevates the European artists over their supposedly hidebound American counterparts. In short, the NYHS exhibition does not do American artists any favors, and all the Armory Show’s complications and contradictions are elided in favor of the shibboleth that the “new” European art revolutionized American culture in one fell swoop.

One noteworthy section positioned amidst the transition to the vaunted European works is a selection of prints by a variety of artists, ranging from John Marin and Stuart Davies to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Edvard Munch. These delightful prints suggest a much more complementary relationship between European and American art than is elsewhere acknowledged.

Still, in arriving at the exhibition’s version of Gallery I, the infamous “Chamber of Horrors” that featured Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 and Henri Matisse’s Blue Nude, it is easy to see why some visitors found these works so surprising in 1913. The NYHS was able to borrow an impressive array of what was regarded as the more sensational art in the Armory Show, but it is of course impossible to resurrect the shock of the new with what are now canonical works. Count me as skeptical that “everyone” was so stunned by these artworks. Recent scholarship suggests that the response to the Armory Show by critics, artists, and the public was much more complicated than the conventional narrative suggests. Moreover, one of the most tired tropes in cultural history and criticism is the idea that X (film, book, album) shocked the world and/or changed everything. As J.M. Mancini, Christine Stansell, and many others make clear, this supposed cultural and aesthetic revolution had a much longer trajectory.

To be fair, some of these complications are addressed around the edges of exhibition, and I can appreciate why the curators stay so focused on the conventional, if flawed, interpretation of the Armory Show to give the exhibition a certain clarity. But other decisions seem less defensible. The end of the main gallery contains a mixed bag of material that confusingly includes some works from J.P. Morgan’s collection in an apparent effort to show that not all contemporary collectors were interested in modern art, which hardly seems surprising. There are also a smattering of works that do not convincingly address the legacy of the Armory Show in American art, though it is a subject that gets more satisfying treatment in the historical materials displayed in the hall adjacent to the main gallery. I really wish that an effort had been made to integrate the very useful and important contextual material in this hall that both sets the scene and explores the legacy of the Armory Show with the actual art. It would have made for a much more coherent interpretation and introduced a level of dynamism that the simple recreation of the original show in smaller form lacked. Of the other ancillary room on “Organizing the Armory Show,” the less said the better about this text-heavy and generally uninteresting display. In sum, I feel like what the Armory Show at 100 needed was to find a better angle, one that would have integrated the Armory Show art with the other materials into a larger story about the development of American modernism. All of that said, the NYHS has assembled a truly wonderful collection of art, and it is well worth a visit. I should also note that the museum has another exhibition open downstairs called Beauty’s Legacy: Gilded Age Portraits in America, which has a rather more satisfying and focused interpretative line and some really excellent portraits so be sure to check that out as well.

Some final notes. The accompanying catalogue, which has a great roster of contributors, undoubtedly deals with some of the complications and criticisms of the exhibition that I offered above, but its size and price ($65!) precluded me from getting a good look. I will update when I do! There are also some great resources online about the Armory Show for those interested. Beyond the aforementioned New-York Historical Society website accompanying the exhibition, the Smithsonian Archives of American Art has a good collection of primary sources here, and the Art Institute Chicago’s has a neat site here about the Armory Show’s sojourn to the Midwest.

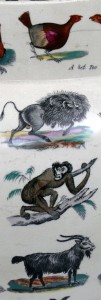

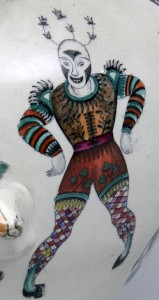

The other day a reader sent in an inquiry about an antique circus jug. It is a truly fascinating piece of mid-nineteenth-century English pottery that was manufactured in Tunstall by Elsmore & Forster sometime between 1853 and 1871.

Tunstall was part of the so-called “Staffordshire Potteries” (modern-day Stoke-on-Trent), a center of ceramic production that developed in the late seventeenth century and which became a hotbed of working class radicalism in the 1840s. Elsmore & Forster seemed to have specialized in this sort of large glazed earthenware jug, which measures 14″ across and 10″ in height. The firm produced several different versions of these jugs decorated with popular entertainment motifs that were “transfer-printed” from wood or metal engravings (see other examples at the V & A here and here).

Tunstall was part of the so-called “Staffordshire Potteries” (modern-day Stoke-on-Trent), a center of ceramic production that developed in the late seventeenth century and which became a hotbed of working class radicalism in the 1840s. Elsmore & Forster seemed to have specialized in this sort of large glazed earthenware jug, which measures 14″ across and 10″ in height. The firm produced several different versions of these jugs decorated with popular entertainment motifs that were “transfer-printed” from wood or metal engravings (see other examples at the V & A here and here).

In this case, the engravings were likely borrowed or purchased from a local printer who used these sorts of illustrations in advertising for circuses and menageries. The assorted animals pictured on the jug are based on the work of artist and engraver Thomas Bewick (1753-1828). As I have written about elsewhere, Bewick’s works of natural history, most notably A History of Quadrupeds (1790), were also frequently copied by American printers and feature prominently in many early menagerie posters. A curious range of animals are represented, including an elephant, a zebra, a tiger, a squirrel, a frog, and several domestic house cats. After the outline of the illustrations was transferred onto the surface, they were colored in by hand before the piece was glazed. The line-up of animals are repeated on each side of the jug with a one or two variations and there are some additional ivy leaf and berry decorations inside of the rim and the spout, and along the main handle.

In this case, the engravings were likely borrowed or purchased from a local printer who used these sorts of illustrations in advertising for circuses and menageries. The assorted animals pictured on the jug are based on the work of artist and engraver Thomas Bewick (1753-1828). As I have written about elsewhere, Bewick’s works of natural history, most notably A History of Quadrupeds (1790), were also frequently copied by American printers and feature prominently in many early menagerie posters. A curious range of animals are represented, including an elephant, a zebra, a tiger, a squirrel, a frog, and several domestic house cats. After the outline of the illustrations was transferred onto the surface, they were colored in by hand before the piece was glazed. The line-up of animals are repeated on each side of the jug with a one or two variations and there are some additional ivy leaf and berry decorations inside of the rim and the spout, and along the main handle.

On either side of the smaller carrying handle there are twin images of a clown, identified by various sources as Joe Cashmore. According to John Turner’s biographical dictionary of British circus performers, Joe’s father was a clown named Ike Cashmore and his mother, billed as Madame Cashmore, was a noted tight-rope performer and equestrian. His full name was Joseph Henry Cashmore, and advertisements printed in The Era (a contemporary trade journal for entertainers) listed his skills as: “Comic Knockabout Clown, High Stilts, Juggler, Running Globe, Vaulter, &c.” The clown is the most technically accomplished illustration on the jug, with intricately detailed clothing and checkered tights that required real skill by the colorist to execute. For more on the fascinating world of the mid-nineteenth-century British circus, see The Victorian Clown by Jacky Bratton and Ann Featherstone. The book centers on a manuscript by a man named James Frowde, who performed with Hengler’s Circus in the 1850s, and offers a wealth of information about what life was like for clowns like Cashmore.

And, if you are interested, this wonderful piece of ceramic circus history can be found here for just $2600!

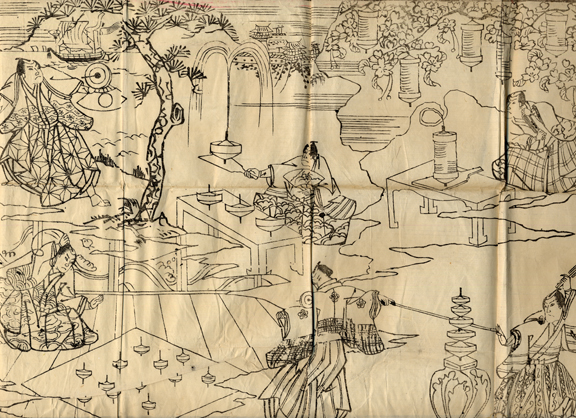

In an earlier post about the American statesman John Hewson Pruyn, I wrote about the role that the American circus performer and impresario Richard Risley Carlisle played in the evolving cultural relationship between the United States and Japan. Risley arrived in Yokohama on March 6, 1864 with a small troupe of performers, and Pruyn initially expressed hope that the circus would help thaw tensions between the Japanese and foreign communities. The show opened on March 28 in front of an audience of around four hundred people, about half of whom were foreign residents. Pruyn was seemingly less than impressed with the circus as a letter dated April 1 noted that “the Japanese admire the clown very much,” but that he was “the very poorest I ever saw.” He went on to sarcastically speak of the relatively expensive tickets as being “exceedingly cheap for so intellectual a performance.” Whatever Pruyn’s opinion, the circus proved popular and a number of Japanese artists made wonderful woodblock prints documenting the show, including this one by Utagawa (or Issen) Yoshikazu.

After its initial success, interest in the circus waned and the performers dispersed, but Risley elected to stay in Japan and pursued a variety of eclectic ventures, including at one point importing dairy cows from California and selling ice cream (for more on Risley’s doings in Japan, see Frederik Schodt’s aforementioned book). But the big idea that he finally hit upon was the realization that the Japanese performers who often entertained the foreign community would be a real novelty abroad. Indeed Pruyn frequently commented on the quality of Japanese entertainment, and he was particularly taken with the characteristic top-spinning performances that he witnessed, which were a novelty to foreigners. Below is a woodblock print that Pruyn saved commemorating a November 14, 1864 performance by a famous top-spinning troupe headed by Matsui Gensui (for a full account of the evening see Francis Hall’s recently published journal).

Woodblock print

1865

Albany Institute of History & Art

Robert H. Pruyn Manuscript Collection, CH 532

Matsui Gensui and those of his ilk were known as misemono, which Schodt translates literally as “things to show” or “exhibitions,” and included sleight-of-hand, balancing, juggling, acrobatics, amongst a range of other entertainments. The obvious popularity of misemono amongst the foreign community led a number of would-be impresarios to consider organizing a troupe to tour abroad, but the Japanese government’s prohibition on overseas travel and raising the necessary capital made such a venture difficult. With the help of the U. S. consul and local American merchants, Risley cobbled together the needed funding and secured permission for what was dubbed the “Imperial Japanese Troupe” to head abroad. In early 1867, the troupe arrived in San Francisco and embarked on a strikingly successful tour across the United States and eventually around the world. As Schodt notes, Risley’s Imperial Japanese Troupe ultimately played a signature role in introducing the then mysterious world of Japan to those in the West. Risley’s activities are a more or less perfect distillation of one of the major themes of my own work, namely how popular entertainment has served as a medium for cross-cultural exchange.

Though we are straying ever farther from Robert Hewson Pruyn, the man whose papers at the Albany Institute of History & Art originally inspired these posts, I want to highlight one last cultural artifact of interest. It is a short motion picture filmed in Thomas Edison’s New York Studio on April 29, 1904 now at the Library of Congress. It shows two Japanese acrobats performing what was by then known simply as a Risley act. It was this foot-juggling routine that catapulted its namesake to fame and fortune, and its performance by two Japanese entertainers aptly illustrates the ongoing legacy of international exchange via performance and popular culture.