One of the things that I am packing up for the move across country is a fine print that I acquired at a garage sale here in Cheesman Park. It is an 1845 aquatint of a trotting horse named Lord William and a delightful example of the widely popular British sporting prints that were produced during the mid-nineteenth century. According to Bent’s Register of Engravings (1846), it was engraved and published in London by J. R. Mackrell after a painting by William Shayer. Prices are listed for both a plain (7s 6d) and colored edition (15s). After a bit of haggling, I paid $20 for this plain version, which I think actually looks better than the color print.

William Joseph Shayer (1811-1892) was an English artist and the eldest son of William Shayer (1787-1879), a noted landscape and figure painter from Hampshire. The younger Shayer specialized in coaching and hunting scenes, but as both signed their works “W.S.” and painted in the same style, there is often some confusion with regards to the attribution of their respective works. Given the subject and date, it seems clear that this particular print was based on an early work by the younger Shayer (and if a reader can point me to the original painting, do let me know). The painting below, descriptively entitled The London to Brighton Stage Coach (ca. 1850), offers a good impression of his typical subject matter and technique.

The pleasing pastoral and sporting scenes painted by the Shayer family made their works popular with printmakers who sought to capitalize on the seemingly insatiable public demand for such images. Hundreds, if not thousands, of different prints after the Shayers’ works were produced in volume in London and beyond during the nineteenth century.

The “Lord William” aquatint was made by a prolific engraver named James R. Mackrell (ca. 1814-1866). As previously noted it was first published in 1845, but some restrikes seem to have been made at a later date. An aquatint is a variety of etching that was invented in France in the 1760s, and its characteristic feature is to give the appearance of watercolor washes. The process involves a copper or zinc plate that is covered with powdered rosin and then progressively etched and bathed in acid to create the desired lines and tonal variations. An intaglio method of printmaking, the resulting incised image is able to hold ink and is then passed through a press with a sheet of paper to produce the final print. The appeal of the aquatint was that it provided printers with a way to more easily create large areas of tone, and the durability of the plates used allowed for large print runs. The distinctive “watery” look of the aquatint proved popular with the public as well, and even after the ascent of lithography in the mid-nineteenth century, aquatints were still being produced in large numbers.

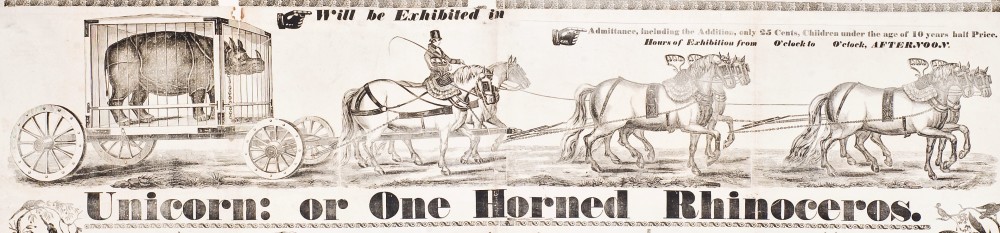

I was initially under the impression that the titular “Lord William” was the driver, and it was only upon closer inspection that I realized that it was the horse. The descriptive text underneath the image indicates that he was the property of one Samuel Lawrence, Esqr., while also noting the following: ‘This Extraordinary animal Trotted a Match against time in harness, for a wager of 200 Sovereigns aside from London to Brighton in the unprecedented time of Three hours and Fifty minutes. October 14th 1842. Driven by the Owner.’ Harness racing, in which horses race at a specified gait pulling a wheeled cart called a sulky, had originated in North American in the late 17th century and the first recorded harness races in Britain were held in 1750. By the mid-nineteenth century, it was a favored form of sport and gambling among gentlemen of means, as the relatively large stakes of this contest suggest. Although races are now held at formal tracks, at the time they were usually staged as single matches between two gentlemen and their steeds over a proscribed road and/or distance. The famed Brighton Road (the modern day A23) was fifty-one and a half miles as measured from the south side of Westminster bridge to the seaside aquarium in Brighton, which was then a fashionable resort. Horses bred specifically for trotting came to be known as “Standardbreds” because they had to be able to trot a “standard” mile in less than two and a half minutes. In his race from London to Brighton, Lord William traveled at a clip of 13.4 miles per hour or a little less than four and a half minutes per mile, an impressive pace given the total distance. Unfortunately, I have been unable to locate a contemporary account of the contest, so this print might serve as the only record of Lord William’s victory.

Sources: Brian Stewart and Mervyn Cutten, The Shayer Family of Painters (1981); Wray Vamplew, The Turf: A Social and Economic History of Horse Racing (1976); for a more recent and entertaining account of horse racing in New York see Steven Reiss, The Sport of Kings and the Kings of Crime (2011)