Last week I went for a photography session at the Penumbra Tintype Portait Studio, which is a project of the Center for Alternative Photography. There seems to have been something of a tintype revival of late, and I was interested in learning more about the process. Tintypes, or ferrotypes as they were sometimes known, were a form of wet plate photography that became very popular in the 1860s. The production process was much simpler and cheaper than other forms of photography and the resulting image was much more durable. Tintype was actually a misnomer as the traditional plates were actually thin sheets of iron. The Penumbra studio used a reproduction camera equipped with a Gascoigne and Charconnet Petzval lens, and the quarter-plate (3 ¼” x 4 ¼”) we had taken was made of aluminum.

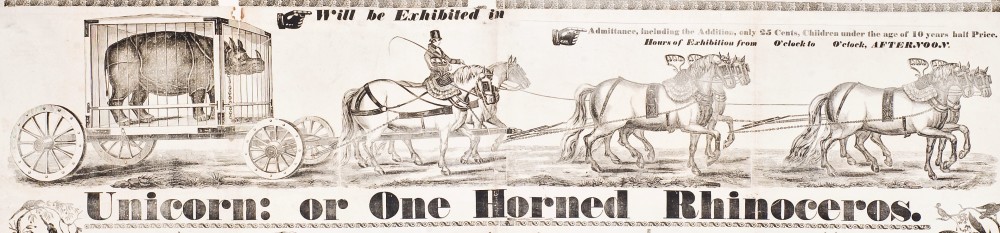

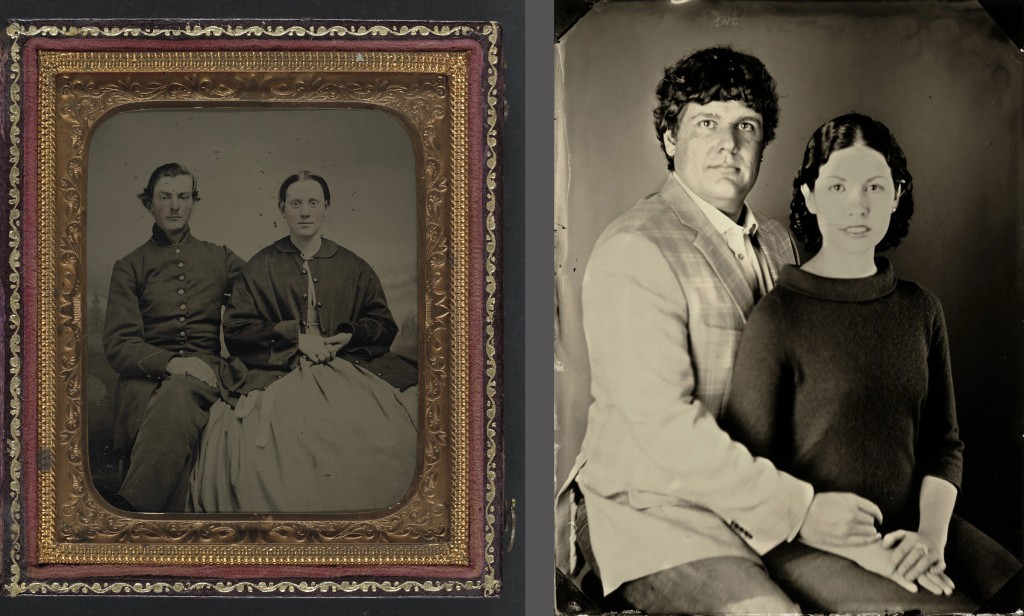

The process itself is relatively straightforward. First, the camera is set up and focused on the subjects. In a darkroom, the plate is wet with thin layer of collodion and then is deposited in a silver nitrate bath. It is light sensitive when removed so it is put in a light-proof plate holder and brought out to the waiting camera. Traditionally, the sitters would have to remain still while the plate was exposed for several seconds, but at the studio modern flash/strobes are used for a more or less instant exposure. The plate is then taken back to the darkroom where a developer is poured on and the image somewhat ethereally emerges before being immersed in a bath for final processing. After drying, the plate is coated with a varnish and you’re all set. Early on, portraits were often placed in fancy cases, but cheaper cardboard and paper frames became more common as the century progressed. The New York Times has a useful slideshow of the overall process here. As you might imagine, the nature of the process and the chemicals involved make it a very inexact art, but even our failed portraits looked pretty cool. Below are a classic Civil War-era tintype of an unidentified soldier and a companion, and then our modern-day portrait.

Because they were so cheap and durable, tintypes were a popular mode of street photography well into the twentieth century. There is a nice shot in the Walker Evans archive of a vendor working a New York City corner circa 1933-34.

Along with a revival of the practice, there have been a number of recent publications and exhibitions about tintypes, though I would still recommend The American Tintype as the best starting point for further inquiry.

Update: The Metropolitan Museum of Art just opened a new exhibition, “Photography and the Civil War,” which speaks to the power and popularity of tintypes at that time.